When an Epidemic Spreads, So Do Rumors

The biggest thing our institutions could do to stop the spread of COVID-19 misinformation would be to spread less misinformation themselves.

Some people thought the disease was a bioweapon. Others were sure the whole thing was a hoax—a story spread, one writer said, so the public would accept "restrictive curbs upon their freedoms." Another tale, fanned at times by the Chinese Communist Party, claimed that the outbreak had actually originated not in China but in the United States. In the U.S. itself, one Asian restaurant after another had to fend off whispers that a staffer had contracted the illness.

If you think those sound like the stories that have circulated since COVID-19 first emerged last year, you're right. But they all come from the SARS outbreak of 2002–03. I lifted them from An Epidemic of Rumors, a 2014 book by the folklorist Jon D. Lee. Lee in turn compared the tales he'd gathered to similar legends from the AIDS crisis.

As these stories recur, they inevitably shift to reflect the specifics of each crisis. Lee notes, for example, that the H1N1 virus of 2009 inspired many more vaccine conspiracy theories than SARS did, probably because an H1N1 vaccine was produced so quickly. But "the nature of the disease itself is almost of secondary consideration," he concludes. "Narratives are recycled from one outbreak to the next, modified not in their themes but in the specific details necessary to link the narratives to current situations."

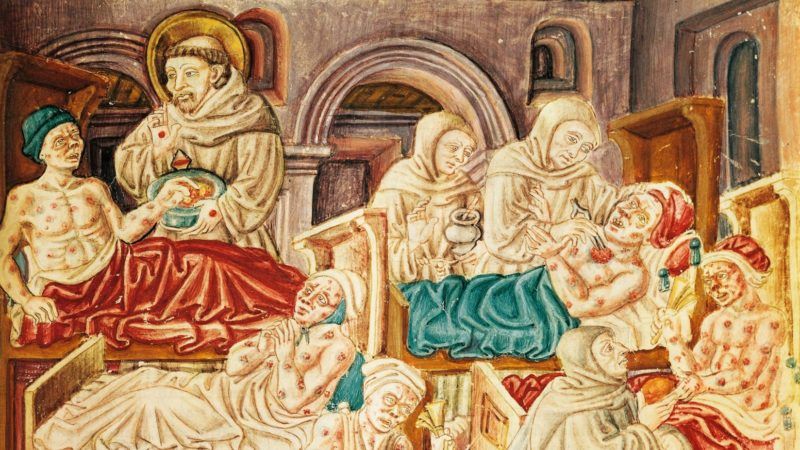

Some of those stories have roots that go back centuries. Long before modern medicine emerged, medieval authorities were blaming outbreaks on the machinations of Jews, or sometimes Muslims, or sometimes even the diseased themselves. In 1321 in France, the country's lepers were accused of conspiring to infect everyone else. According to the historian Carlo Ginzburg, summarizing the account of the Dominican inquisitor Bernard Gui, the purported plotters had allegedly "strewn poisonous powders in the fountains, wells and rivers, so as to transmit leprosy to the healthy and cause them to fall ill or die." As the story spread, lepers were arrested, imprisoned, compelled to confess, and burned.

Deliberate disinformation goes back centuries too. The authorities may well have launched that legend of the leprous conspiracy, and they certainly fanned the fear once the story took hold. Those efforts paid off when the revenues from the lepers' asylums were seized for the royal treasury.

It shouldn't be surprising that tales like these take off when especially deadly or disfiguring diseases are on the loose. Any period of heightened anxiety is going to produce fearful rumors. Some of those rumors will be absurd, but others will seem plausible; sometimes, as we'll see below, they'll even have some truth to them.

When those anxieties recede, the stories they sparked often disappear from public memory. And so, when another crop of anxieties appears and the old stories resurface in new skin, they're widely seen as something novel. Today rumors travel through social media, and so they are often mistaken for a product of social media. They're clearly much older than that.

That's worth keeping in mind as Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms try to crack down on COVID-19 misinformation. It turns out that all those other ways of communicating haven't gone away; we can still forward emails and text messages. So now the counter-disinformation crowd is worrying about the "hidden virality" at work in private networks they can't see, and NBC is warning us that "there's no sense of how widespread the rumors are, making them harder to rein in." In Kashmir, where the Indian government has shut down internet access since last summer, the inability to go online has made the information ecology less reliable: Karl Bode reports in TechDirt that "rumors and dis/misinformation are spreading quickly via Whatsapp and word of mouth, with no ability for citizens to research and confirm the claims." Maybe rumor-mongering and conspiratorial fears haven't been more common in the social media era after all; maybe they're just easier to observe.

At any rate, we shouldn't focus a disproportionate amount of attention on the stories sprouting from the grassroots. The biggest thing that governments and media outlets could do to stop the spread of COVID misinformation would be to try a lot harder not to spread misinformation themselves. Some inaccuracies are inevitable, especially in the foggy early days of a pandemic, but the failures this time around have been stunning. That's especially true in China, where the authorities tried to cover up the outbreak when they should have been sharing what they knew, but it's true in more open societies too. In the U.S., the most preposterous moment of official misinformation might have been when the president misstated his own policies in a March 11 address, with disastrous consequences. But there have been plenty of other sad examples, even setting aside the deception machine in the Oval Office.

"It is difficult to express how badly almost all legacy 'expert systems' simultaneously underperformed during the initial phases of the crisis," writes Adam Elkus, a PhD student in computational social science at George Mason University. Meanwhile, he adds, "the global COVID-19 response depended on an enormous amount of information developed and shared often in defiance of traditional media." If you can't always trust official sources, you can't always reject the rumor mill either. Sometimes it knows things that the official sources don't.

And that's been true for a long time too.

"Last week there were rumors that an exotic new disease had hit the gay community in New York," the New York Native announced in May of 1981. It was the first sentence of the first known press report about the disease that would come to be called AIDS. The article didn't predict the plague to come: It interviewed an official from the Center for Disease Control—that's what CDC stood for back then—and assured everyone that the stories were "for the most part unfounded."

The CDC soon realized that this was wrong, and within a few weeks it would be offering a rather different story. The press followed suit. But before the mainstream media, before the CDC, before even that gay newspaper in New York, there were those rumors. They hadn't been relaying an urban legend that time. The street had sensed something happening.

______________________

ADDENDUM: This article originally quoted a Twitter thread by the disinformation researcher Renee DiResta to show how these recurring legends are sometimes framed as an artifact of the "the social-media-news era." DiResta writes to clarify that she is aware that such stories are not new and that she has often written about their pre-internet roots elsewhere.