How the 'No Hate. No Fear.' Marchers Are Fighting Anti-Semitism

"We're here because we have to play offense and defense against this growing hate in this country and in this world."

"Ten thousand," says the New York City cop, when I ask how many people the city's expecting at the No Hate. No Fear. Solidarity March, an event in protest of a rise in anti-Semitic attacks, primarily against Orthodox Jews, in the New York City area.

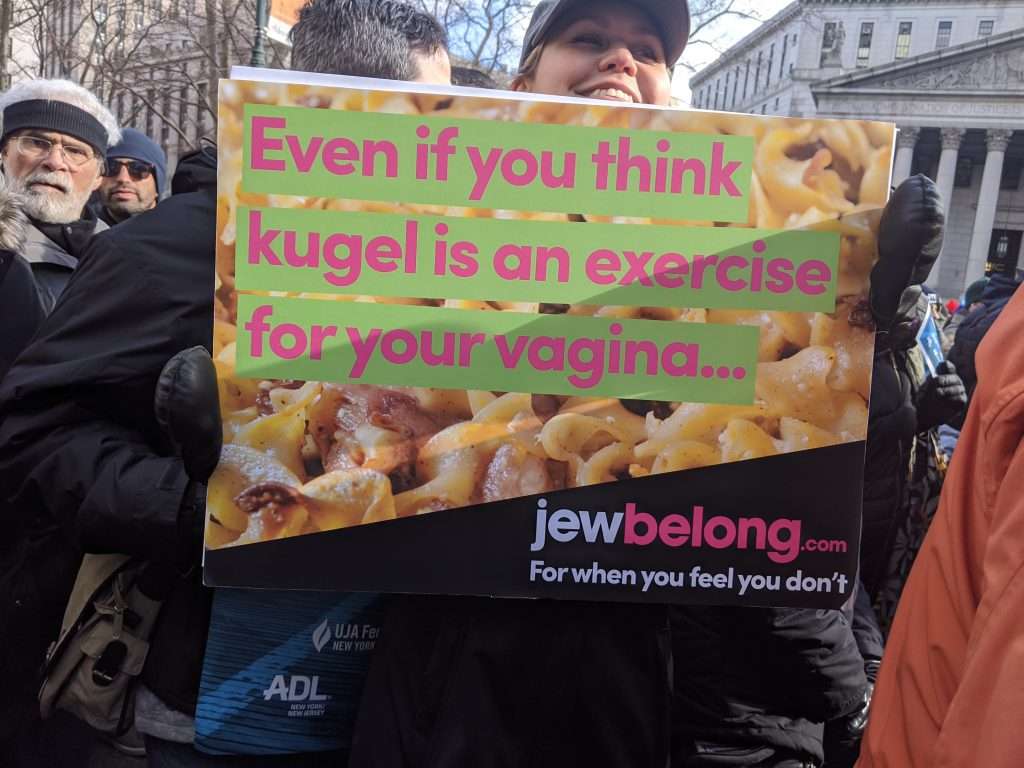

He can't yet know that an estimated 25,000 will show or that the march, from Foley Square in Lower Manhattan over the Brooklyn Bridge, will be over capacity from the get-go. An hour before march time and the streets are packed solid, people wrapped in Israeli flags and carrying American flags, wearing Yankee caps and yarmulkes, carrying signs that read NO HATE NO FEAR and babies in bunting to keep out the kind of cold where you expect birds to drop from the sky, the kind of cold in which you don't normally see sixty-something women chattering outdoors about the HBO series Big Little Lies and men standing on a park bench drinking coffee and calling out, "Hey, you a reporter? He gives good quotes."

Sure. Why are they here today?

"We're here because we have to play offense and defense against this growing hate in this country and in this world," says Ariel Nelson. "That means not just standing by and making sure our synagogues and our institutions are secure, but going out en masse and showing the world that we are not going to tolerate it."

"It" being the rise in hate crimes against Jews: 229 last year according to city officials, including a pair of gruesome incidents in December, the murder of four people in a Kosher supermarket in Jersey City, and a man with a machete storming a synagogue during a Hanukkah celebration in Monsey, 35 miles north of New York City. The two attacks got a lot of airtime, the others (some seen in a sickening compilation video), not so much. There are reasons to take some of those statistics with a grain of salt. Does Nelson, who works for a news organization, see the media downplaying the attacks?

"Yes," he says.

Does he have an opinion as to why?

"Jews aren't important," he says. "That's just the way of the world, and it's unfortunate."

"I had been under the view that antisemitism was mostly a thing of the past in the post-Holocaust era," says David Leit. "In recent months and years, my view has changed, and I think that antisemitism now requires a much more robust response. Whereas previously I thought that maybe some groups were overreacting to it, now I tend to agree more with Ariel, that if anything, we've been underreacting."

Which makes it easy, or easier, for people not immediately affected to see the attacks as just a thing happening in New York.

"Pittsburgh isn't New York," says Nelson. "Poway isn't New York."

"Paris isn't New York!" says Leit.

"And New York is where you would think it shouldn't happen," adds Nelson. "I mean, New York, there's lots of Jews here, it's the most pluralistic place on Earth, practically. You would think there would be, if anything, greater ability to get along. And my understanding is that the current New York police statistics [show] that half of the reported hate crimes [in 2019] are against Jews, which is shocking."

A drum boom starts from somewhere.

"There can be skepticism about marches, like, 'We're all going to get here, and we're going to chant,' and does it actually accomplish anything?" says Nelson. "In some respects, that's a fair criticism. But I think there also does need to be public displays of unity…whether you're Jewish or not Jewish, whether you're black or white, whether you're Muslim or Christian, we should all be here together today, to say, we're not going to tolerate it."

The people who are not going to tolerate it include a handful of young people singing a pop song in Hebrew as they walk amidst many thousands toward the bridge. Where are they from?

"Israel!" say two 18-year-old girls at once. They're volunteering with the Jewish Agency for Israel, working with Jewish communities in Brooklyn. Have they noticed an escalation in violence in the five months they've been here? Yes, they say.

"Honestly, I think we are better prepared in terms of, we know how it feels like to be under attack, to be alert all the time," says one. "But I don't think we have better tools to deal with terror attacks and anti-Semitism."

"Now people understand how this situation in Israel is," says the other. "We experience it in Israel and now it's starting to be here and people feel it and now they actually will do something about it."

And then they go on singing, being joyful despite the knowledge that massacre might be coming for them. But then, what are the options?

"I myself this week filled out an application for a gun permit," says David Katz, who's running for Congress from New York District 17 in Rockland County, which includes Monsey, where the machete attack occurred and where Katz grew up.

"I was taught to be worried about stuff like this, and then as I got older, I realized, it's not such a danger. Now it seems like it is a danger," he says. "There's more of a nervousness, and for myself––excuse my French––shit seems to be happening and I want to be prepared in the event there's a much larger conflagration. Does that make sense?"

Yes. During the Monsey attack, one of the Orthodox men picked up a table and attacked the assailant with that, which, granted, was impressive, but a gun would be a little more—

"Right," says Katz. "There was a celebration for a new Torah within a couple of days after that, and there were Jews with guns presenting weapons. I know there are plenty of people that have already been training with weapons, preparing."

How big of a shift is it for the Orthodox community to arm themselves?

"Is the culture changing? That's a yes," he says. "Especially in younger people, at least. I think there's a change in thinking, like, 'there is a danger and we can't count on anyone to protect us in the moment.' Yes, police will come at some point. But in the moment, we are targets."

For which the targets are sometimes blamed, as in, if Jews had not formed a community in Monsey, or wherever, there would be no friction with those not of the community and thus no opportunity, no incubator per se, for hatred of Jews to grow. Which history tells us, over and over, is untrue. People can crochet hatred out of nothing. How do we fight a hatred that never seems to go away for good, that comes back every generation with a new virulence? With new people ready to embrace hate and justify what they do with it, and a world willing to watch and prevaricate?

"Do we need to be shot dead in a synagogue for people to pay attention to the fact that our neighbors are being beat up?" asks Bari Weiss on-air with CNN, as she starts walking across the bridge. An opinion page editor at The New York Times and author of the recent book, How to Fight Anti-Semitism (and, full disclosure, a friend), Weiss has written heartbreakingly of the attack at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where she made her bat mitzvah and where, in October 2018, a gunman entered yelling, "Death to all Jews!" and killed 11 people.

Not today, no death today, today is about believing we can make this about life, we have made it across the bridge to Cadman Plaza Park, where a young man enthusiastically approaches my friend and asks if he's been "tied" yet today. My friend, who's flown in from Austin, Texas, for the march, says no, and the young man wraps the leather tefillin up his arm, telling us at a rat-a-tat pace how overjoyed he is by the day, that we are all here together, he has my friend say a few words and then asks, "You're Jewish, yes?" My friend says he's not, he's Episcopalian, and the young man smiles and says, "Well, it's your bar mitzvah" and, after loosening the ties, walks toward the massive Brooklyn War Memorial, with its larger-than-life figures symbolizing victory and family, and on which in a few minutes Weiss will stand before thousands and explain why she is a Jew, and why we are here. She tells us, "We are the lamplighters, we are the ever-dying people that refuses to die. The people of Israel live now and forever, Am Yisrael Chai."

Show Comments (37)