Aaron Sorkin, Mark Zuckerberg Feud Over Political Ads. Here's Why Sorkin's Wrong.

Plus: The ACLU sues the FBI, divorce rates are at 40-year low, and more...

Aaron Sorkin versus Facebook: The West Wing and Social Network writer scolded CEO Mark Zuckerberg in an "open letter" in The New York Times yesterday. Essentially, Sorkin accused Zuckerberg of contributing to the decay of American democracy and being a hypocrite about free-speech principles, after Facebook chose not to remove an untruthful Trump campaign video and said it wouldn't be in the business of policing truth in candidate ads.

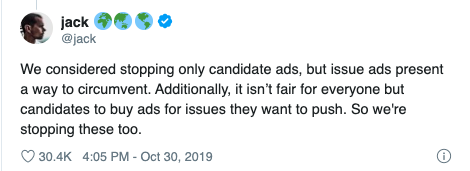

The dustup comes the same week that Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey announced that his company will stop accepting paid ads for political campaigns or political issues at all.

Both mark a growing culture war over how social media content should be moderated and regulated.

The Sorkin op-ed in the Times was notable for several reasons. First, it featured the preening moral indignance and self-righteous scolding Sorkin is known (and loved or hated) for. For instance:

I admire your deep belief in free speech. I get a lot of use out of the First Amendment. Most important, it's a bedrock of our democracy and it needs to be kept strong.

But this can't possibly be the outcome you and I want, to have crazy lies pumped into the water supply that corrupt the most important decisions we make together. Lies that have a very real and incredibly dangerous effect on our elections and our lives and our children's lives.

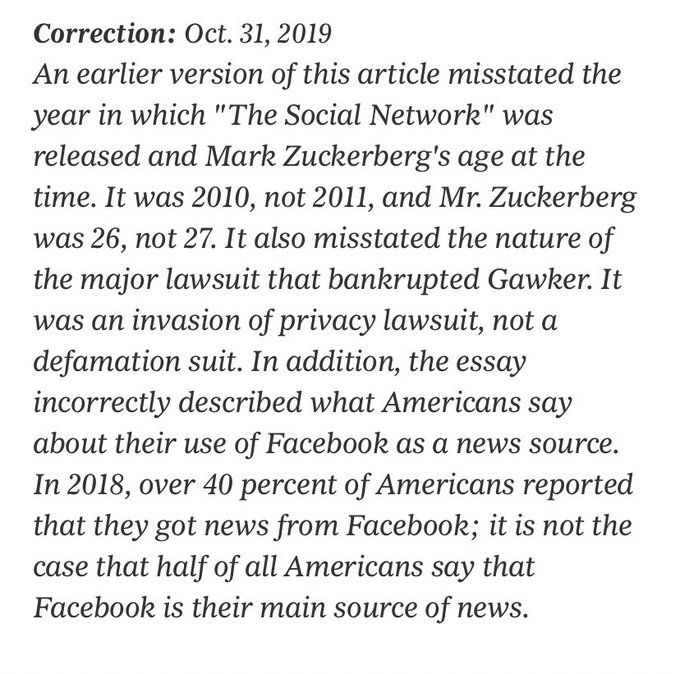

It also needed three factual corrections, including one on a relatively significant point about American consumption of news from Facebook. (Also, Sorkin got the year of the release of his Facebook film wrong.)

Sorkin's piece makes an oblique reference to Section 230, alleging (falsely) that there's no way to hold digital sites and services accountable for user-generated content. ("The law hasn't been written yet—yet—that holds carriers of user-generated internet content responsible for the user-generated content they carry, just like movie studios, television networks and book, magazine and newspaper publishers.") It thus continues the Times' apparent inability to cover Section 230 and the moderation of user-generated content without having to issue corrections.

For the record, Facebook makes a lot of decisions that I disagree with and some that I loathe, but I think it's right not to set itself (and its massive force of low-paid content moderators) as the arbiters of online truth. Decentralization of knowledge production and information dissemination is one of the greatest gifts of the internet, and it can still be accomplished to greater or lesser degrees even within closed systems (such as Facebook or Twitter).

Twitter's decision to ban paid political content may sound sensible at first—that's the company's own ad money to lose, after all—but the logistics will be a nightmare. What makes an issue or idea "political"? Who decides?

Private internet companies can of course "censor" and censure and deplatform pretty much whomever they wish. But tough-on-content policies, attempts to censor ideas (not just obviously illegal content), and many of the excessively hands-on approaches that people advocate these days are a recipe for ensuring that grassroots voices, minority communities, and outside-the-status-quo ideas stay marginalized.

As an example: I help run a small, basically no-budget, nonprofit group called Feminists for Liberty. Since Facebook implemented its policies to crack down on "foreign influence" and fake political actors, we've had to jump through increasing hoops to have our Facebook page even exist. So far, we've been prevented from promoting events on the platform because we didn't have the right government form to submit to Facebook's inspectors. There must be many groups (and candidates, and causes) like ours, getting blocked by policies ostensibly meant to help promote freedom of expression and ideas online.

Meanwhile, bigger players (including those with nefarious goals) have little problem complying with new policies like these, and they can usually pay to find workarounds for major shifts. From search engine optimization to increasing social reach to building brands on TikTok and whatever's next, big players (in politics, business, entertainment, or whatever) have employed—and will continue to—whole teams of scientists, journalists, consultants, and others to figure out how to game algorithms, increase the appearance of "organic" reach, and so on.

On Twitter, major political players will find ways to get their messages seen regardless of whether they can promote posts. Smaller and less mainstream voices who may need a little paid promotion to get started or to stand a chance against massive entrenched industry groups or political parties will be the ones who lose out.

As Nick Gillespie notes, both Facebook and Twitter "are clearly responding to threats by legislators seeking to regulate social media." (See, for example.)

"The differing approaches to the issue of paid speech provide a good opportunity to discuss not just how political communications work in a post-broadcast world but also how the internet is falling short of its promise to radically alter the way people communicate and connect," writes Gillespie. Twitter's policy "represents a near-complete lack of faith in users to function as critical consumers of information" and "a fundamental betrayal of the ideals that helped build the internet into an unparalleled, open system of knowledge and information."

QUICK HITS

- ACLU is suing over FBI facial tracking.

- The White House has picked a new acting secretary of the Department of Homeland Security.

- Minnesota won't let Trump's primary challengers on the ballot.

- Divorce rates in the U.S. reached a 40-year low last year. "The divorce rate was 15.7 divorces per 1,000 married women in 2018, down from a divorce rate of 16.1 in 2017," reports Colette Allred, looking at recent U.S. Census Bureau data.

It seems our politics are often dominated by the idea that everything is getting worse. It's not. In many ways things are much, much better than the recent past. It's vital that we tell a balanced story about American realities -- bad AND good. https://t.co/fzZlPfbQYD

— David French (@DavidAFrench) October 31, 2019

- The historic St. Regis hotel in New York City was just sold to Qatar.

- Huh:

BREAKING: North Carolina House and Senate Unanimously Vote to Close Consent Loophole.

We will no longer be the only state in the country where a woman cannot revoke consent to have sex once sex has begun.

It took five years of filing the bill over and over, but we got it done.

— Rep. Jeff Jackson (@JeffJacksonNC) October 31, 2019

- Here's your periodic reminder that Section 230 (the federal law shielding online operators from some liability for some types of user-generated content) has repeatedly kept people from winning lawsuits like these:

Man Sues Twitter For $1 Billion Claiming His Account's Suspension Violated His Right To Worship President Trump As A Demigod https://t.co/Ydb87E4Pqh

— techdirt (@techdirt) November 1, 2019

Show Comments (159)