As Opioid Prescriptions Surged in Germany, Opioid Addiction Held Steady, While Opioid-Related Deaths Fell

The data reinforce the point that there is no straightforward relationship between pain pill consumption and overdoses.

Contrary to the conventional narrative of the "opioid crisis," it is clear from U.S. data that there is no straightforward relationship between narcotic analgesic prescription rates and deaths involving those drugs, or between the volume of analgesics prescribed and the incidence of misuse or addiction. A recent study sheds further light on this issue, finding that "the number of persons addicted to opioids in Germany has hardly changed over the past 20 years," notwithstanding a sharp increase in opioid prescriptions that began in the 1990s.

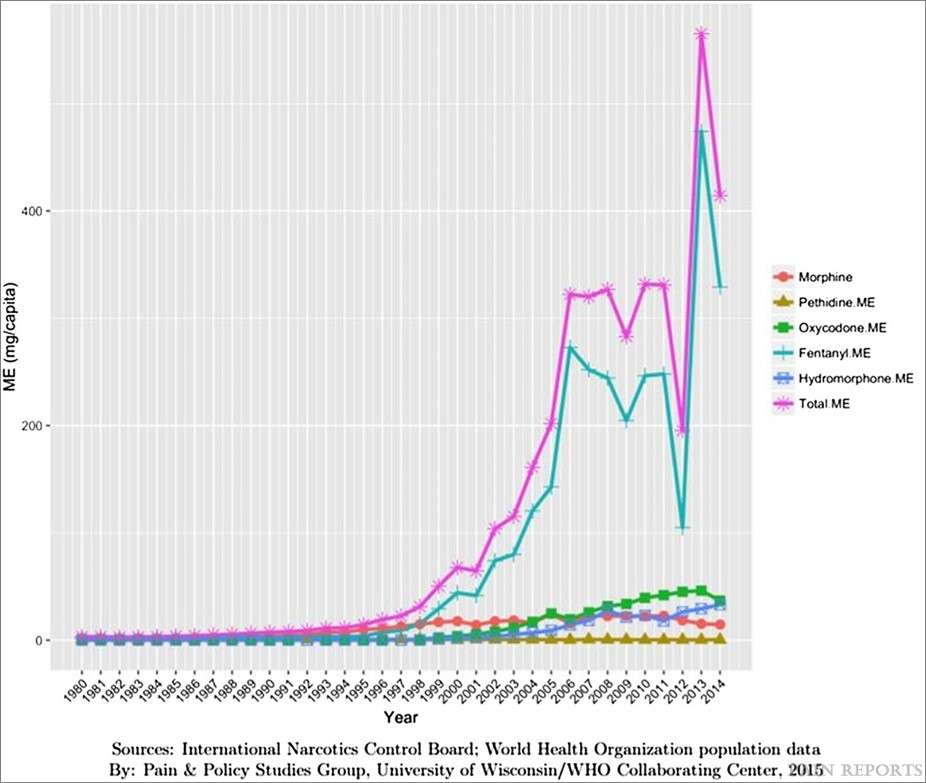

Here is a chart showing the volume of opioids prescribed by German doctors, measured in morphine milligram equivalents per capita, from 1980 through 2014:

That comes from a 2017 article in the journal PAIN Reports. The newer study, published last March in Deutsches Arzteblatt International, estimates that in 2016 there were 166,294 "opioid-addicted persons in Germany." The researchers add that "comparisons with earlier estimates" indicate the number was about the same two decades before then, prior to the dramatic increase in opioid prescriptions. In other words, a large increase in consumption of narcotic pain relievers did not lead to a surge in addiction, whether to those drugs or to illicit opioids such as heroin.

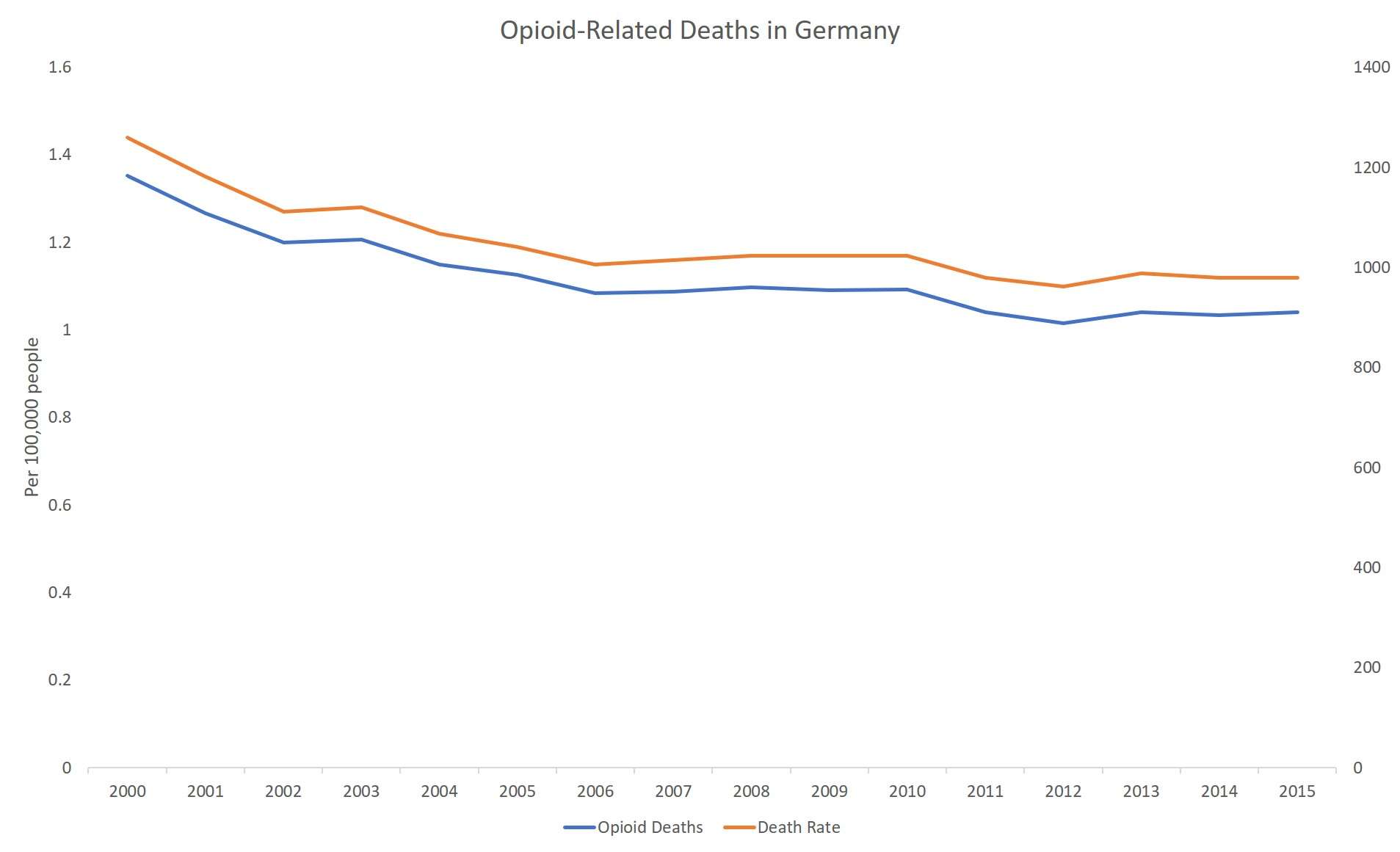

What's more, OECD data compiled by J.J. Rich, a policy analyst at the Reason Foundation (which publishes this website), show that deaths involving licit and illicit opioids did not rise in Germany either. In fact, both the number of deaths and the death rate declined during the same period when prescriptions were climbing.

"There are signs of an opioid epidemic in Australia and Canada, but not in Germany," the authors of the 2017 PAIN Reports study concluded after looking at data from those three countries, all of which have seen big increases in opioid prescriptions during the last two decades. According to the OECD data, total opioid-related deaths fell in Australia from 2000 through 2006, then rose from 2007 through 2015, when the number was about the same as it was in 2000. In Canada, opioid-related deaths rose steadily from 2000 through 2012, then fell for the next three years. Yet in Germany, opioid-related deaths were declining or steady throughout that period.

What makes Germany special? Its regulations and guidelines, as described in the PAIN Reports study, seem pretty similar to those in Australia and Canada. One notable difference in prescribing guidelines is the daily dose at which "particular caution" is recommended, which was lowest in Australia and highest in Canada, with Germany in the middle. The study notes that "fentanyl patches are the most frequently prescribed strong opioids in Germany," and such products may be less appealing to nonmedical users than pills that can be swallowed or crushed and then snorted or injected.

But it seems clear that other factors are at work, including social and cultural conditions that make addiction more likely or less likely. "The US leads the developed world in per capita opioid-related overdose deaths, while Germany's overdose rate is among the lowest in the developed world," notes Phoenix surgeon Jeffrey Singer, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, who brought both of these studies to my attention. "Germany's overdose rate has been essentially unchanged for most of this century. Opioids were considered responsible for just under 800 overdose deaths in 2016, compared to more than 42,000 deaths in the US that year."

The vast majority of those opioid-related deaths involved heroin or illicit fentanyl. The U.S. has a population four times as big as Germany's and an opioid problem more than 50 times as big.

There are also significant drug policy differences between the two countries. "Unlike the US, Germany has embraced harm reduction strategies for the treatment of substance use disorder and non-medical drug use for decades," Singer writes. "These strategies include safe injection facilities, needle exchange programs, medication assisted treatment and heroin assisted treatment, and distribution of test strips and naloxone."

Even if the U.S. copied German harm reduction policies, drug use would still look different in the two countries, because it is influenced by many variables beyond the substances themselves or the policies aimed at controlling them. But those policies can make drug use more dangerous or less dangerous, depending on the priorities of the people who formulate and execute them.

Show Comments (23)