The NSA Defended the Domestic Surveillance That Snowden Exposed. Now the Agency Wants to End It.

After years of political fights over our privacy, a potential end in mass phone metadata collection

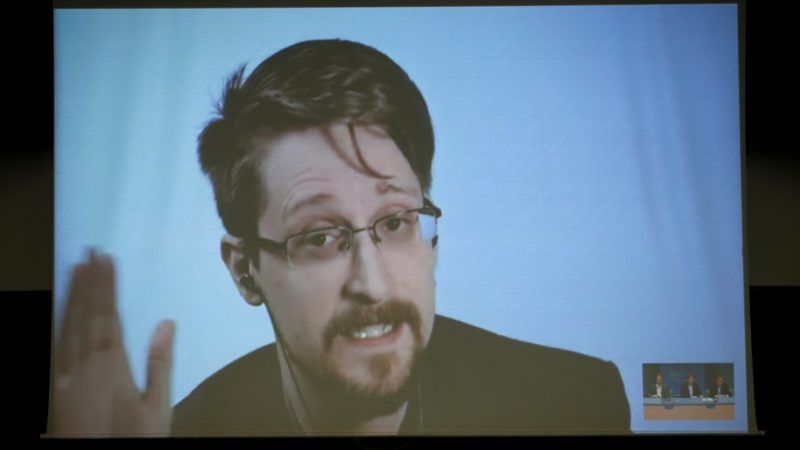

Almost six years after Edward Snowden revealed to the American public that the National Security Agency (NSA) was collecting millions upon millions of telephone records without warrants or cause, the agency itself is calling for an end to the practice.

Officials loudly defended the practice at the time, insisting it all was necessary to keep America safe from terrorists. After a political fight, compromise legislation known as the USA Freedom Act allowed the data collection to continue but kept the information in the hands of the telecom companies and put restrictions on NSA agents' ability to access Americans' phone metadata (essentially everything except the actual content of their conversations).

But the NSA reportedly stopped trying to access these phone records earlier in the year, and now The Wall Street Journal reports that the agency says it doesn't want the program any more. That's a big deal, as the powers granted by the USA Freedom Act are up for renewal this year.

There are a few likely reasons why this is happening. First: Though officials kept insisting that the authority to collect these records was vital to tracking down terrorism, it has yet to be credited for catching any terrorists or stopping any terrorist acts. Second: The NSA has found itself collecting massive amounts of private data that it acknowledges it's not allowed to have, forcing it to purge its records. Third: In the time since the NSA first launched this surveillance—back in 2001, when the PATRIOT Act was passed—smartphone users have shifted away from communicating through voice conversations and are more likely to use apps (particularly encrypted ones) to communicate via texting.

If the USA Freedom Act goes away, that doesn't mean that the federal government will lose all its authority to snoop on Americans. Just last year, Congress and President Donald Trump renewed and expanded the feds' powers under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act to secretly surveil Americans for wholly domestic criminal matters.

Should the White House accept the NSA's recommendation here and let the USA Freedom Act expire, that makes it all the more important that we pay attention to governments' efforts across the world to force social media platforms and app makers to introduce backdoors to encryption or some other form of structural weakness that would allow government spies to access our private communications without our knowledge.

This fight is heating up now that Australia has passed expansive, intrusive legislation that essentially forces people who work at or run private communication platforms or apps to assist Australian officials in secretly bypassing encryption. Australia has an intelligence-sharing agreement with the United States, so anything it gathers could be passed along to the feds. Microsoft has warned that it may stop storing data in Australia entirely to keep officials there from forcing the company's employees to give them access to private data.

One avenue of secret, unwarranted surveillance appears to be closing. But the struggle to protect our privacy from government snoops is far from over.

Show Comments (38)