How Congress Could Stop Trump's Trade War, and Why It Might Not

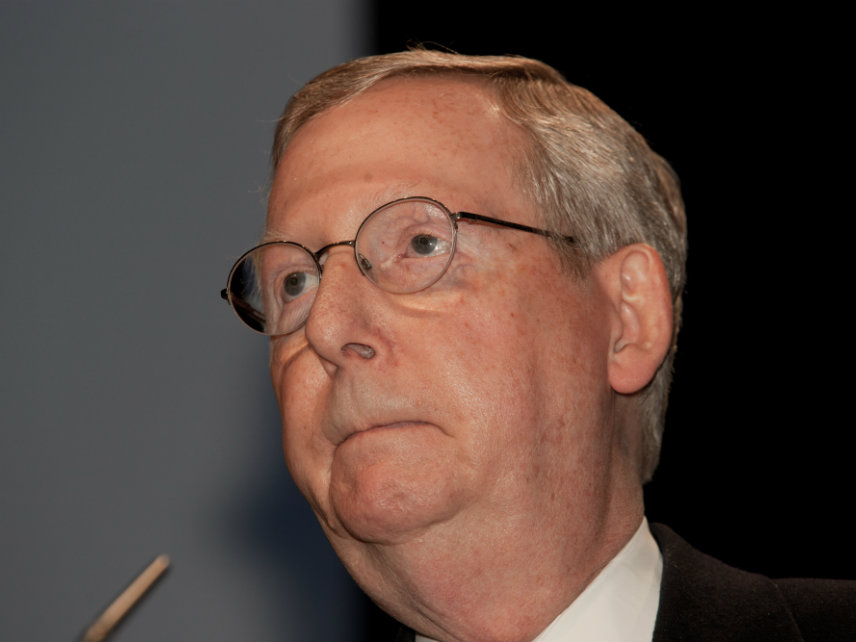

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell says he's "nervous" about getting into a global trade war. Here's what he could do to prevent one.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell reportedly told Kentucky farmers and business leaders this week that President Donald Trump's trade policies could create a "slippery slope" that "can't be good for our country."

"I'm not a fan of tariffs, and I am nervous about what appears to be a growing trend in the administration to levy tariffs," McConnell said Tuesday, according to the Louisville Courier-Journal.

Tariffs on steel and aluminum issued last month by President Donald Trump will do significant damage to a wide range of American industries, from farming to housing to manufacturing, that will have to pay higher prices for those materials. Trump followed those tariffs by calling this week for a 25 percent import tax on some 1,300 Chinese-made goods. If approved by the U.S. Office of the Trade Representative, those tariffs will force American businesses and consumers to pay higher prices for almost everything, including necessities like food and clothing. Reciprocal tariffs imposed by China will hurt American farms and businesses a second time, and Trump has already threatened an additional $100 billion in tariffs as a tit-for-tat to China's response.

No wonder, then, that McConnell says he is "nervous about getting into trade wars and I hope this doesn't go too far."

If only he were in a position to do something about it, right? He could, of course, and there's several ways Congress could push back against the White House's protectionist trade policies—but there may not be consensus on what to do, and Republican leaders so far seem unwilling to cross Trump, even as he pursues a course that's unclear in its aims and risks doing serious damage to the economy.

Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the explicit power "to lay and collect taxes, duties," and the like. Although the legislative branch has delegated much of its authority over trade and tariffs to the executive branch in the past century, it could take steps in the next few months to restore those original powers and check Trump's dangerous protectionist impulses. It will have at least one major opportunity to do so, thanks to a June 30 deadline for the reauthorization of one such provision delegating trade power to the White House.

Timing is a factor for other reasons too. Republican lawmakers that could face Trump-backed primary opponents are unlikely to want to break openly with the White House on trade. As spring turns to summer and primary season passes, that's less of a concern.

"Congress will have leverage, but it seems like they've been unwilling to use it," says Dan Ikenson, director of trade policy studies at the libertarian Cato Institute. "It has more leverage today than it had a month ago, and that leverage gets stronger as the general election approaches."

The first round of tariffs—the ones issued in early March and applying to imported steel and aluminum from a variety of orgins—were imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which gives the president more or less carte blanche to impose tariffs on national security grounds. Officially, the Trump administration says that American weapons of war depend on steel and aluminum supplies, so domestic producers must be protected from international supplies that could be cut-off in the event of a conflict.

That's a weak rationale for a whole slew of reasons, but it exists, and under Section 232, that's enough. Congress could threaten to revoke Section 232 or modify it through new legislation. There is precedent for this—Congress overturned Jimmy Carter's national security restrictions on oil imports in 1980—but it would veto-proof majority and is therefore unlikely to happen.

The newer tariffs, issued by Trump last week and applying to a wide range of Chinese-made products, are a far easier target for Congress if lawmakers want to get serious about preventing a trade war.

The second round of tariffs were issued under Section 302 of the Trade Act of 1974, which allows the White House to initiate an investigation into supposedly unfair trade practices by another nation and to respond with tariffs if they are deemed appropriate. The United States has not used Section 302 since joining the World Trade Organization in 1995, because membership in the WTO requires that member states bring trade disputes before the organization rather than acting on their own.

Trump doesn't seem to care that his tariffs will flout WTO rules, but the breadth of tariffs issued last week could trigger political pushback from lawmakers. Unlike tariffs that narrowly target steel and aluminum—politically favored industries that lawmakers running for reelection want to appear friendly towards—the political ramifications of new tariffs on biscuit ovens, airplane parts, sewing machines, brewery equipment, and hundred of other items could swing the other direction, particularly since red states figure to bear the brunt of the tariff impact.

If Congress decided it wants to put the brakes on Trump, the June 30 deadline to reauthorize the president's Trade Promotion Authority will be crucial. Under TPA, the White House is authorized to fast-track trade deals with other countries by negotiating them without congressional interference. Congress pledges to hold a straight up-or-down vote on the final product, essentially promising that it won't try to alter or undermine whatever deal the president makes.

Congress granted TPA to President Barack Obama in 2015, and the authority remains in place for six years—but there's a catch. After three years, Congress can exercise an option to revoke that authority. While revoking Trump's TPA would not directly block tariffs, it would make it harder for the president to make unilateral trade deals with other countries—something Trump has clearly, and repeatedly, said he wants to do—and therefore could be used as a pressure point against the administration.

A more dramatic option would be to pass Sen. Mike Lee's (R-Utah) Global Trade Accountability Act, which would require congressional approval before tariffs could go into effect. The bill would also give Congress the ultimate authority on whether to withdraw from other trade agreements including NAFTA and the WTO, says Clark Packard, trade policy counsel for the R Street Institute, but would not apply to the steel and aluminum tariffs issued under Section 232.

Even though Trump's tariffs could do significant damage to the American economy and cause the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs, Congress may be reluctant to step in because members believe there is something to be gained from Trump sparring with China.

Indeed, even as he was scolding the White House for triggering a trade war that will hurt farmers, Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) this week defended the idea of imposing tariffs as a way of combating China's history of abusing trade rules and international norms. "The United States should take action to defend its interests when any foreign nation isn't playing by the rules or refuses to police itself," said Grassley. "But farmers and ranchers shouldn't be expected to bear the brunt of retaliation for the entire country."

Tough trade talk could be a "healthy shock to the global trading system" that makes China shape up and stop abusing the system for its own economic advantage, says Edward Alden, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Behind all the bluster, this may be the goal that the Trump administration is pursuing. But Trump has so far been unclear about what it is he hopes to achieve—and while his inattention to policy details have has caused problems in the past, the stakes have never been as high as they are now. That's exactly why Congress should be pressing the White House to limit tariffs, or at the very least to make it clear what terms they would accept from China to deescalate the pending trade war.

"Other than broad complaints about a series of longstanding Chinese practices such as intellectual property theft and forced technology transfers, the administration has not issued any clear demands," says Alden. "It is vital that Trump officials communicate their goals and intentions clearly and provide a path to a resolution. Otherwise, there is a serious danger that events could spiral out of control."

Even with clear goals and intentions, Trump's tariffs chart a dangerous course for the economy. Congressional action on trade does not have to constitute a direct confrontation with the White House, but if Trump is going to lead the country down this reckless path, it is imperative for congressional leaders like McConnell and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) to exert whatever power than can to limit the damage. Even if there is not consensus on what to do—and there very well may not be a majority in either chamber willing to fight the White House on trade—it is important to make the effort.

Certainly, it requires more than having the most powerful man in the Senate wringing his hands together and muttering about how "nervous" a trade war makes him feel.

The tariffs proposed by Trump already cover about $100 billion out of a $650 billion annual trade relationship. More retaliation from China and another $100 billion in American-imposed tariffs, as Trump suggested this week, would surely represent a point of no return.

"That would kill both economies," says Ikenson. "It would kill the global economy. It really would be bad news."

Show Comments (77)