To Cut Taxes Now, Republicans Promise to Raise Them Later

Will Congress tackle entitlement spending and agree to raise taxes in the mid-2020s? If not, the deficit will get even bigger than some projections show.

Votes are expected Tuesday in the House and Senate on the final version of the Republican-crafted tax reform bill. Unless there's a truly shocking final twist, it appears that the bill will be headed to President Donald Trump's desk within the next 24 hours or so.

The president is understandably excited.

As the world watches, we are days away from passing HISTORIC TAX CUTS for American families and businesses. It will be the BIGGEST TAX CUT and TAX REFORM in the HISTORY of our country! pic.twitter.com/EvcAkjuf8w

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 18, 2017

But the GOP tax bill comes with a big price tag. And after peeling back a few layers, that price tag gets even bigger.

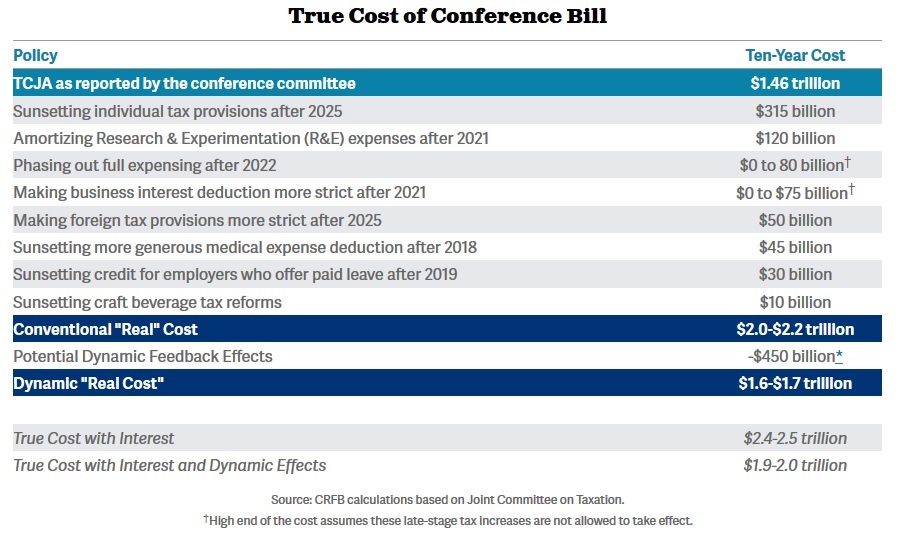

Officially, the tax bill is expected to add about $1.5 trillion to the national debt over the next decade, though the "cost" of the tax reform effort is about $1 trillion once expected economic growth is factored into the equation.

There has not been a single estimate released by Congress, the White House, or any independent tax policy group that suggests the tax bill will "pay for itself," as Republican leaders for so long promised it would.

One thing all those estimates have in common is that they say the tax bill will add to the national debt. Another thing they have in common is potentially under-estimating how much will be added to the debt by taking certain parts of the bill at face value.

The GOP tax plan attempts to game those projections in a few significant ways. The personal income tax cuts included in the bill, for example, are set to expire in 2025, two years before the end of the 10-year window used for budget projections. There's an important practical reason for the $1.5 trillion threshold too, because the tax cuts must comply with the Senate's Boyd Rule that prohibits passing bills with a simple majority if they add to the long-term deficit (Republicans cleared about $1.5 trillion in budget space earlier this year, with tax reform intended to fill that gap).

But to meet that threshold now, the GOP has to promise to increase taxes later.

Getting a better sense of what the tax bill will actually cost requires gaming out what future congressional majorities and administrations might do when faced with the prospect of raising taxes on all Americans in 2025. Business friendly tax cuts for so-called "bonus depreciation" will begin expiring as soon as 2022. Other future tax increases included in the bill include the end of tax breaks for craft brewers and for employers who offer paid leave.

Taken together, these gimmicks could add as much as $600 billion to the final cost of the tax plan, according to the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. That brings the final price tag of the tax plan up to about $2.2 trillion, before factoring in potential economic growth.

Republicans are saying, essentially, is the tax bill costs only $1.5 trillion as long as future Congresses agree to follow through with the parts of the bill that would trigger big tax increases near the end of the next decade. There are good reasons to be skeptical that will happen. Congress is generally far more eager to cut taxes than to raise them.

The current tax reform bill is an exercise in avoiding fiscal accountability. Republicans like Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), who have talked for so long about the danger poised by our $20 trillion national debt and stressed the importance of cutting spending, are now essentially saying that they'll get around to fixing the debt right after adding to it.

In its assessment of the tax plan, the Treasury Department waved away concerns about increasing the debt. The tax bill will be paid for by "a combination of regulatory reform, infrastructure development, and welfare reform," the Trump administration says, as if passing any of those things will be an easy accomplishment. If you're going to believe Congress is that close to a complete overhaul of the welfare system, then I suppose you might as well believe it will raise taxes in the mid-2020s, too.

There is still a very real ethical argument against increasing the debt. "Borrowing now pushes costs to the future," Chiris Edwards, the Cato Institute's director of tax policy, told Reason TV earlier this month. "From a libertarian perspective, you can see the pain is moved to the future when the government borrows more now, and that's unethical."

Letting people and businesses keep more of the money they earn is undeniably a positive outcome of the Republican tax plan, of course. The big picture, though, is far less sunny.