Instead of Filling Vacancies, Congress Should Abolish the NLRB

The NLRB's "arbitrary and capricious" decision-making no longer represents the interests of the public. It's been politicized to the point of no return.

The U.S. Senate voted earlier this month to confirm Marvin Kaplan's appointment to the National Labor Relations Board, filling one of two vacancies on the five-member panel charged with setting policy for union elections and for adjudicating conflicts between union workers and employers.

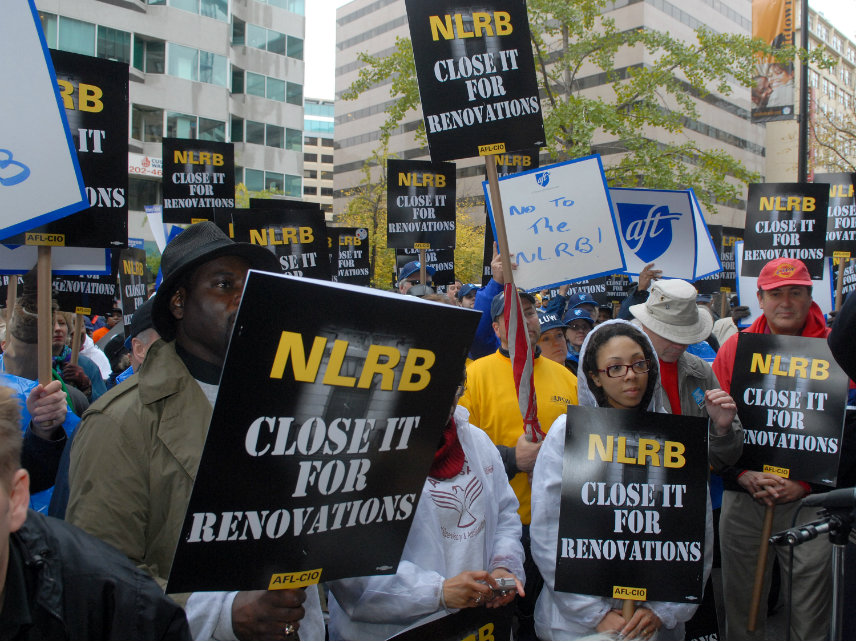

Rather than fill the other vacancy on the highly politicized board—which operated with only three members during most of the Obama administration because Senate Republicans refused to confirm appointees—perhaps Congress should do away with the board altogether.

Created in 1933 as part of the National Industrial Recovery Act, a Depression-era law that gave the president sweeping authority to institute wage and price controls, the NLRB existed to settle sometimes-violent disputes that erupted between unions and employers. It is well past time to recognize the fundamental flaws in the NLRB, which have led the board to become politicized and partisan, says says Trey Kovacs, a labor policy analyst with the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington, D.C.

"The NLRB was created to be impartial government members that represented the public interest in labor disputes. That no longer happens," Kovacs says. "Democrats and Republicans basically appoint labor lawyers or employment lawyers who favor one side or the other, so it no longer represents the public interest."

The NLRB is a quasi-judicial body, but hardly operates like one. Courts look to past rulings when making decisions. The NLRB is guided not by precedent, but by the whims of the board members. Outcomes tend to go in one direction or the other, depending on the ideology of the majority.

"Case precedent flip-flops depending on which party is in power," says Kovacs. "So they don't really exercise any expertise, just their political will."

With a 2-1 majority of Democratic appointees during the Obama administration, the board handed down a number of decisions favorable to labor unions. It allowed for the creation of so-called "micro unions" within workplaces. It dramatically shortened the length of time between when a union calls for an election and when that election is held, allowing for "ambush elections" in workplaces. The move was criticized by employers who complained they no longer had enough time to state their case against unionizing before an election.

Appointing someone to the board has become as or more contentious than getting someone appointed to a federal court. Republicans issued an ultimatum to President Barack Obama in 2015 refusing to confirm additional members unless Obama nominated a candidate approved by the GOP. He declined.

Had Hillary Clinton won the White House last year, it's easy to imagine a continued standoff. It's also easy to see some future Democratic-controlled Senate refusing to confirm appointees from a Republican administration. Indeed, the vote on August 2 to confirm Kaplan as the NLRB's fourth member was straight down party lines, and Democrats like Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., took to the Senate floor to condemn what she saw as "a new anti-worker nominee."

That degree of politicization leaves the NLRB gridlocked and unpredictable in the long term. Whether you favor business or labor, that's no way to make policy or settle disputes.

Kovacs suggests labor law cases go directly to federal court, where judges are beholden to precedent and are unlikely to be appointed specifically because they favor one side or the other in worker-employer disputes.

In a telling ruling issued the day before Kaplan's confirmation, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a NLRB decision in favor of eight union reps who had been arrested for who occupying and refusing to leave a Portland, Oregon, grocery store in 2009.

The NLRB saw it as "unfair labor practices." The NLRB's review of the case was "disingenuous" and carried out "in an arbitrary and capricious manner by failing to engage in reasoned decision-making," wrote Judge Janice Rogers Brown. "In short, the Board's actions in this matter are more consistent with the role of an advocate than an adjudicator."

If the NLRB cannot perform its functions without being bogged down in partisan interpretations of matters of fact, and if appointments to the board cannot be made without raucous fighting designed to further politicize the NLRB, perhaps it is time for Congress to shut it down completely.

Listen to my conversation with Trey Kovacs on this week's edition of American Radio Journal here.

Show Comments (17)