Here Are All The Things Idaho's Governor Got Wrong About Asset Forfeiture in His Veto Statement

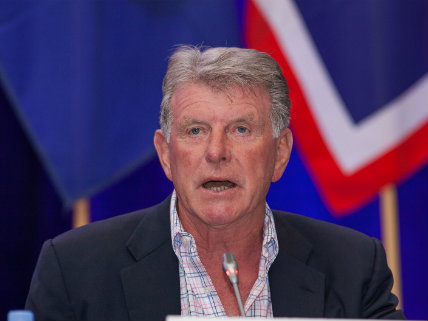

Gov. Butch Otter says cops never abuse asset forfeiture, but there's no way for anyone to know without this bill becoming law.

As he vetoed a bill that would have made it more difficult for Idaho cops to seize property and cash from innocent people suspected of drug crimes, Gov. Butch Otter said the measure was a "solution in search of a problem."

Sure, there might be plenty of examples of law enforcement in other states abusing civil asset forfeiture laws, but police in Idaho would never do something like that, Otter said.

"There have been no allegations that Idaho law enforcement officers or agencies are illegally or inappropriately seizing property from alleged drug traffickers," Otter wrote in his veto message. The bill, which passed the state legislature with broad support from both Republicans and Democrats, was supposed to prevent the improper seizure of assets, "but there is no evidence to suggest that such a problem is imminent," the governor wrote.

Otter is wrong about that. In fact, he's wrong about several things that he said in his veto message.

Otter is playing semantics with the claim that police aren't doing anything "illegally." Of course it's not illegal. No one is arguing that it is illegal to seize assets from suspected drug traffickers in Idaho, only that it should be (at least until those suspected drug traffickers are tried and convicted).

As for the claim that those seizures are inappropriate, well, that's a bit more open to interpretation. Contrary to what the governor says, there have been allegations that Idaho law enforcement officers are using asset forfeiture inappropriately.

Consider the incident reported last year by the Twin Falls Times News. The newspaper reported that deputies of the Twin Falls County Sheriff's Office received a tip about drugs being sold from a home in Twin Falls, Idaho. After raiding the house, the deputies found "a small amount of marijuana and a glass pipe with brown and black residue in a dresser," and a more thorough search of the house turned up another small bag of marijuana and $12,010 in cash.

The couple who lived in the house claimed that the money was from a small business they ran, making and selling candles and other religious items. Maybe they were telling the truth, and maybe they were drug dealers, but the police never bothered to find out.

No criminal charges were ever filed against the couple, the Times News reported, but the deputies took the cash anyway, later claiming that it was "contraband, the fruits of a crime, or things otherwise criminally possessed." (the Twin Falls Sheriff's Department later returned $3,000 after the couple challenged the seizure in court).

Similar stories were brought up during the legislative debate over the bill, but Otter either didn't bother to listen, or he didn't care.

Though asset forfeiture laws can be used to seize cars, homes, and other valuable property, perhaps the most pernicious way those laws have been abused is in the taking of small amounts of cash. When property is seized, owners have to go to court and prove their innocence in order to get it back. When small amounts of cash are seized, owners have little incentive to go through an expensive and time-consuming fight to get it back.

Take, for example, what we know about how law enforcement in Philadelphia abused asset forfeiture laws for years. A review by the City Paper in 2011 found that the median seizure was only $178, despite claims by the local police and prosecutors that asset forfeiture was helping stop major drug deals.

It's the same in other places. A Reason investigation published in January found that police in Mississippi routinely seize petty cash (and even old sofas) from innocent people who never get charged with a crime. In one instance, cops in Mississippi seized just $75.

Is what happened in Twin Falls, Idaho, in 2010 an aberration from the norm? Is that the one and only instance where police took money or property from an innocent person who was never charged or convicted of a crime? It's a bit hard to believe that, considering that Idaho's state law allows police to keep the proceeds of forfeiture, something that the Institute for Justice, in a 2015 report on asset forfeiture, said creates "a strong incentive to forfeit property."

I emailed Otter's spokesman on Tuesday to see if the governor knew about the Twin Falls incident when he proclaimed that police in Idaho never use asset forfeiture laws inappropriately, or if he views that sort of activity to be appropriate. I have not received a response, but will include it here if I do.

Other parts of his veto message don't match with reality either.

For example, Otter claims twice that asset forfeiture is used against "drug traffickers" and "drug dealers," but that's a partial misrepresentation of Idaho's state laws. Indeed, the reforms passed by the legislature this year (and vetoed by Otter) would have restricted forfeiture to cases where the police were investigating trafficking, but the current state law allows law enforcement to seize assets and property for possession—a lower caliber crime. And, again, we're talking about the mere suspicion of drug possession.

Additionally, Otter claims that he vetoed the asset forfeiture reform bill because of the "absence of any benefit to law-abiding citizens." This is maybe the most laughable argument of all, since the whole purpose of the bill is to prevent law-abiding citizens from having their cars, cash, and property taken by police without the cops first proving that a crime was committed.

"The way the current law reads, property of innocent people can be seized and forfeited if present at the scene of a crime at the time of a drug arrest, and no accounting must be made to anyone regarding how the proceeds are used or spent," Tom Arkoosh, a Boise-based criminal defense attorney, told Reason via email. Arkoosh, who lobbied in favor of the bill for the Idaho Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, said the bill passed by the legislature would have fixed "fundamental flaws" with that law.

The real kicker in all of this is the complete lack of accountability that Arkoosh references. Under Idaho state law, we have no way to know how often police use forfeiture (and neither, for that matter, does Otter), but the reform bill vetoed this week would have instituted an annual reporting requirement.

The governor called that requirement "a misplaced effort to hold those responsible for protecting us from crime more accountable while relieving those charged with committing crimes of a worrisome consequence."

Add that to the list of Otter's questionably accurate statements. More accountability for law enforcement is hardly a bad idea, and an annual report tallying up how often asset forfeiture is used should be the bare minimum expected of our law enforcement personnel. If police are going to have the authority to seize assets, cash, and property with impunity—and without first charging anyone with a crime and proving his or her guilt—then residents of the state should, at the very least, know how often the police are exercising that authority.

"Reform opponents cannot claim there is no evidence of a problem while, at the same time, block bills that would require law enforcement agencies to report what they seized, how much they gained from forfeiting property and if they even filed any criminal charges," said Lee McGrath, legislative counsel for the Institute for Justice, in a statement about Otter's veto.

Only with that knowledge can we fully judge how asset forfeiture laws are being used—or abused—in Idaho.

Gov. Otter believes the police and sheriffs of his state never abuse asset forfeiture laws. The record shows he's wrong about that in at least one instance, and until he's willing to introduce some transparency into the process, that belief means nothing.

Show Comments (16)