In Bowling Green 'Massacre,' FBI Agents Foiled an FBI Terror Plot

A 2011 "terrorist plot" in Kentucky is oft used to warn against Muslim refugees. But the only terrorists in this case were manufactured by the FBI.

Fresh off of making-up a massacre on national television, Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway has been trying to rationalize her rhetoric—a rant about how the media didn't cover Obama's refugee ban after the "Bowling Green Massacre" of 2011—by claiming that what she meant to say was "Bowling Green terrorists." While there may not have been a terrorist "massacre"—or any terrorist violence at all—in Bowling Green, Kentucky, there was a terrorist plot uncovered, Conway noted Friday on Twitter, quickly shifting the spotlight back to the supposed danger posed by Islamic refugees.

Conway is correct about a few things: there were two Bowling Green men arrested for terrorism; they were Iraqis who had come to the U.S. through a refugee resettlement program; and their story did prompt then-President Obama to slow or suspend Iraqi-refugee immigration for around six months. But there are a few other key things to keep in mind about this Bowling Green "terrorist plot"…

1. It was concocted entirely by the FBI.

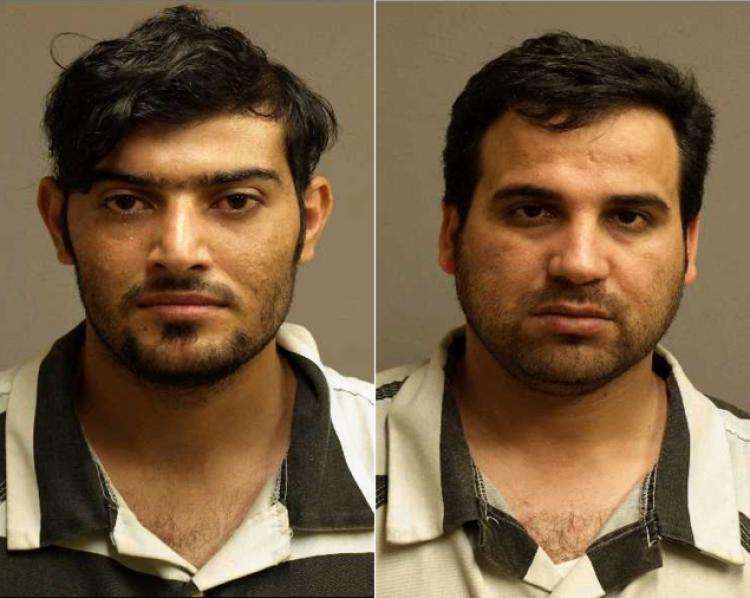

The young men involved, Waad Ramadan Alwan and Mohanad Shareef Hammadi, had come to the U.S. in 2009 as part of a program for displaced Iraqis. Once settled in Kentucky, the men were solicited by undercover FBI agents to help them send money and weapons to militants back in Iraq.

In August 2010, a confidential FBI informant first met with Alwan and "represented to Alwan that he was working with a group to ship money and weapons to Mujahadeen in Iraq," according to an FBI statement. From that fall through the following spring, the FBI informant invited Alwan to participate in 10 operations to send weapons or money to Iraq. Hammadi joined in the efforts, recruited by Alwan, in January 2011. Throughout the operations, the FBI supplied all materials and took care of all logistics for the imaginary operation, with Alwan and Hammadi merely offering manpower.

Despite the FBI's then-assertion that Alwan and Hammadi were just the tip of the terrorist-cell iceberg in small-town Kentucky, the agency never found additional terrorist agents in the area.

2. It did not involve plans to attack in the U.S.

Back in Iraq, Alwan and Hammadi had been involved efforts to fight off invading U.S. soldiers during the early days of the Iraq war, according to what they told undercover officials. But throughout their interactions with undercover FBI agents in 2010 and 2011, Alwan and Hammadi never discussed plans to attack anyone or cause destruction on U.S. soil. And while they were found guilty of attempting to provide material support to al Qaeda militants back in Iraq, the men never indicated that they were personally in contact with any militants, attempted to procure weapons for such individuals, or attempted to provide any of their own money to such individuals. Rather, they showed up when and where the FBI informant told them to and helped physically load decoy supplies into whatever they were allegedly being shipped from. (For more on the FBI's history of manufacturing terrorists like this, see here.)

3. It's in rare company.

According to the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute, only three of the 784,000 refugees cleared for U.S. resettlement since 2001—the two Bowling Green men and a male refugee from Uzbekistan—have been arrested for terrorism or plotting terrorist acts. The Uzbek man, Fazliddin Kurbanov, had come here with his parents as Christian refugees who were being persecuted for their religion in Uzbekistan. But once in the U.S. for a few years, Kurbanov converted to Islam. He was convicted in 2015 for possessing unregistered explosives and attempting to provide money and computer support to the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. Kurbanov was sentenced to 25 years in federal prison. Hammadi was sentenced to life in prison, and Alwan to 40 years.

As Ronald Bailey noted here in 2015, there have been several other terrorism arrests attributed to refugees, such as the Tsarnaev brothers, better known as the Boston Marathon bombers. But the Tsarnaev brothers weren't admitted to the U.S. as refugees but as the minor children of adults granted asylum. "The distinction between refugees and asylees is not just a legal technicality," explains Bailey. "Aslyees are self-selected—they show up at or within the border and apply for asylum. As long as the asylum application is pending, they cannot be thrown out of the country. In contrast, refugees are generally designated as such by U.N. officials, and they usually live in refugee camps. They go through a vetting process that takes up to two or three years."

There may be slightly more rogue refugees than the Migration Policy Institute estimates. There was also Mohamed Osman Mohamud, "the would-be Portland Christmas bomber" of 2010, who came to the U.S. as a 5-year-old with parents who were either refugees or asylees; he was turned in to the FBI by his father. And Ramiz and Sedina Hodzic, two of six Bosnian immigrants indicted in 2015 for allegedly sending money to ISIS, were also admitted as refugees when they were children. Yet as Bailey notes, Kurbanov, Mohamud, and the Hodzics were all radicalized after coming to America. "None of these people, be they refugees or anything else, were sleeper agents who intentionally remained inactive for a long period, established a secure position, and then struck. None, in other words, fit the scenario being bandied about to justify keeping the Syrians out."

4. It's been used to support anti-refugee sentiment ever since.

Following news of Alwan and Hammadi's arrests, the Obama-administration State Department slowed the processing of Iraqi refugee visa applications to a near-halt for several months. Since then, this "Bowling Green terror plot" has resurfaced several times when politically convenient. In 2015, Sen. Rand Paul (R-Kentucky) used it as fodder for why we needed to block Obama from allowing in additional Syrian refugees. Now it's being used by the Trump administration to justify the president's recent executive order temporarily banning immigration from seven countries.