Will Maine Be the First State Where Voters May Rank Their Choices?

Proposition could boost election chances for third-party candidates in some cases.

What if you really didn't have to accept that there are only two valid choices for a particular race, and your third-party vote actually mattered more than as just a protest?

Maine voters may find out for themselves. On their ballot this November is Question 5, a ballot initiative that would institute ranked-choice voting for statewide positions like governor and for lawmakers on both the state and federal levels.

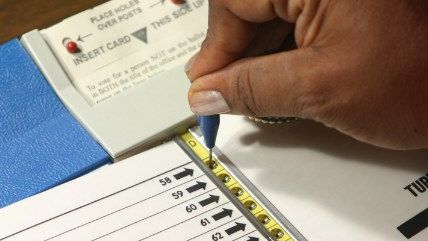

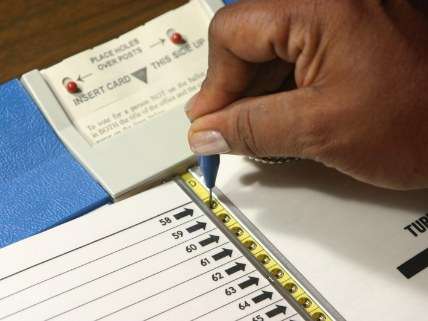

In a ranked vote system, voters are invited not to just check off the box for their favorite candidate; they're allowed to rank each candidate in order of preference. If the winning candidate doesn't get a majority of the votes, there's an "instant runoff." The candidate with the least votes is dumped from the race and the votes are counted again. On the ballots of those who voted for the least-popular candidate, their second choice is now counted as their vote. If again the winning candidate still doesn't get a majority of the votes, the cycle continues until the top-ranked candidate doesn't get just the most votes but a majority of votes.

No state here currently has such a voting system, but some cities do, and it's how Australia elects its lawmakers. Australia's complicated, preference-based voting system has resulted in several lawmakers who are members of smaller parties, including libertarian David Leyonhjelm. That is partly the intent of this system: To make it more possible for third-party candidates to break through the electoral duopoly, but only in situations where the majority of voters reject what the establishment offers.

The editorial board of the Portland Press Herald endorsed Question 5 last week with the awareness that an increasing number of voters are refusing to identify as Democrats or Republicans:

Our current system took shape when there were two strong parties that dominated the political process. Parties won elections by assembling coalitions and selecting candidates who had broad appeal. It was hard for fringe elements to break through.

But even though Maine's political parties have been in decline for decades, they still have an outsized influence on the process. Nominees selected by the small number of committed partisans who show up to vote in June have enormous institutional advantages on Election Day in November.

That puts the largest group of voters, those who are not active as either Democrats or Republicans, in a bind.

They have no say in the selection of a party nominee, but they can't vote for a third-party candidate without risking a vote for a "spoiler" who fragments opposition and gives an extreme candidate a path to victory.

What if, for example, you could vote for Gary Johnson as your first choice, but thought that Hillary Clinton would be much less dangerous as president than Donald Trump (or vice-versa)? You could make Johnson your first choice and Clinton your second. Thus, you'd be shutting down any arguments (or even your own fears) that a vote for a third-party candidate was ultimately helping Trump (or Clinton) win.

Heck, given the unpopularity of Clinton and Trump and the way polls are going, it is likely that the winner in November will get a plurality of the votes, not a majority. A ranked system significantly favors third-party candidates in situations where voters are really unhappy with what the establishment has to offer. It's easy to imagine Johnson becoming the second choice for a good chunk of voters, and then imagine what could happen next if neither Clinton nor Trump gets 51 percent of the majority vote.

It shouldn't come as a surprise then that Johnson supporter and former Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic is a big endorser of this kind of voting system. And he puts his activism where his mouth is: He's the chairman of the Board of FairVote, a nonprofit group pushing for more proportional voting systems such as Maine's proposed ranked-choice method.

The ranked-choice system comes with its own flaws. One study pointed out that even in a ranked-choice election, the winner may not actually have gotten the majority vote in the end. That's because voters don't have to rank all candidates. They can just rank the one (or ones) they legitimately want to vote for. If that candidate gets the least amount of votes and cut from the instant run-off, the vote becomes meaningless. So in the presidential example, if we had a four-way race including Green Party candidate Jill Stein, it's likely Stein would get the least amount of votes (based on current polls) and would be cut in the next round of vote tabulations. That means every vote that was only for Stein and did not rank other candidates would get tossed and would no longer "count." The outcome may sometimes be that the winner still really only got a plurality of the votes, not a majority. But it may well be a different person than who got the plurality of votes in a simple count.

But ultimately it's hard to explain why this is any different from the winner-takes-all system we have now. All votes for Stein are likely to be irrelevant in this election. Most votes for Johnson probably won't "matter" either, except maybe in a couple of pivotal states. At least in a ranked system, third-party voters could express their primary choice but also, if they wanted to, register a "lesser of two evils" vote for a Democrat and Republican and feel maybe slightly less disappointed in the election outcome.

Right now two polls show Question 5 receiving more support than opposition, but the most recent poll has a very high number of undecided voters (23 percent). This will be a ballot initiative to watch on Election Day.

Below, watch ReasonTV's interview with Novoselic in 2014 where he talks extensively about improving electoral representation:

Show Comments (49)