Lancet Commission Recommends Drug Legalization

As the U.N. prepares for a special session on "the world drug problem," 22 experts catalog the costs of prohibition.

The last time the U.N. General Assembly held a "special session" (UNGASS) on drug policy, it was organized under the slogan "A Drug-Free World…We Can Do It." Pino Arlacchi, then executive director of the U.N. Drug Control Program, insisted "there is no reason" the world's supply of cocaine and heroin "cannot be eliminated in little more than a decade." That was 1998. With a new UNGASS on "the world drug problem" scheduled for next month, a group of 22 experts organized by The Lancet and Johns Hopkins University is hoping to inject a little more realism into the proceedings, including an awareness of prohibition's human costs and the benefits of "mov[ing] gradually towards regulated drug markets."

The report of the Johns Hopkins–Lancet Commission on Drug Policy and Health, published in the medical journal last Thursday, faults U.N. officials for conflating drug use with drug abuse, a black-and-white, all-or-nothing attitude that leads not only to vacuous slogans but to highly punitive, violently repressive policies that do far more harm than good. "The authors of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) 2015 annual report concluded that, of an estimated 246 million people who used an illicit drug in the past year, 27 million (around 11%) experienced problem drug use, which was defined as drug dependence or drug-use disorders," the commission says. "The idea that all drug use is dangerous and evil has made it difficult to see potentially dangerous drugs in the same light as potentially dangerous foods, tobacco, alcohol, and other substances for which the goal of social policy is to reduce harms. Harm reduction, an essential element of public health policy, has too often been lost in drug policy making amid a dominant discourse on the overwhelming evil of drugs."

Harm reduction aims to minimize the damage done by drug control policies as well as the damage done by drugs themselves. Prohibition magnifies the hazards of heroin use, for example, by creating a black market in which potency is unpredictable and encouraging both injection (because that's the most efficient route of administration and prohibition makes heroin artificially expensive) and needle sharing (through laws that limit access to syringes and punish possession of them). As a result, heroin users are more likely to die from overdoses or blood-borne diseases than they would be if heroin were legal.

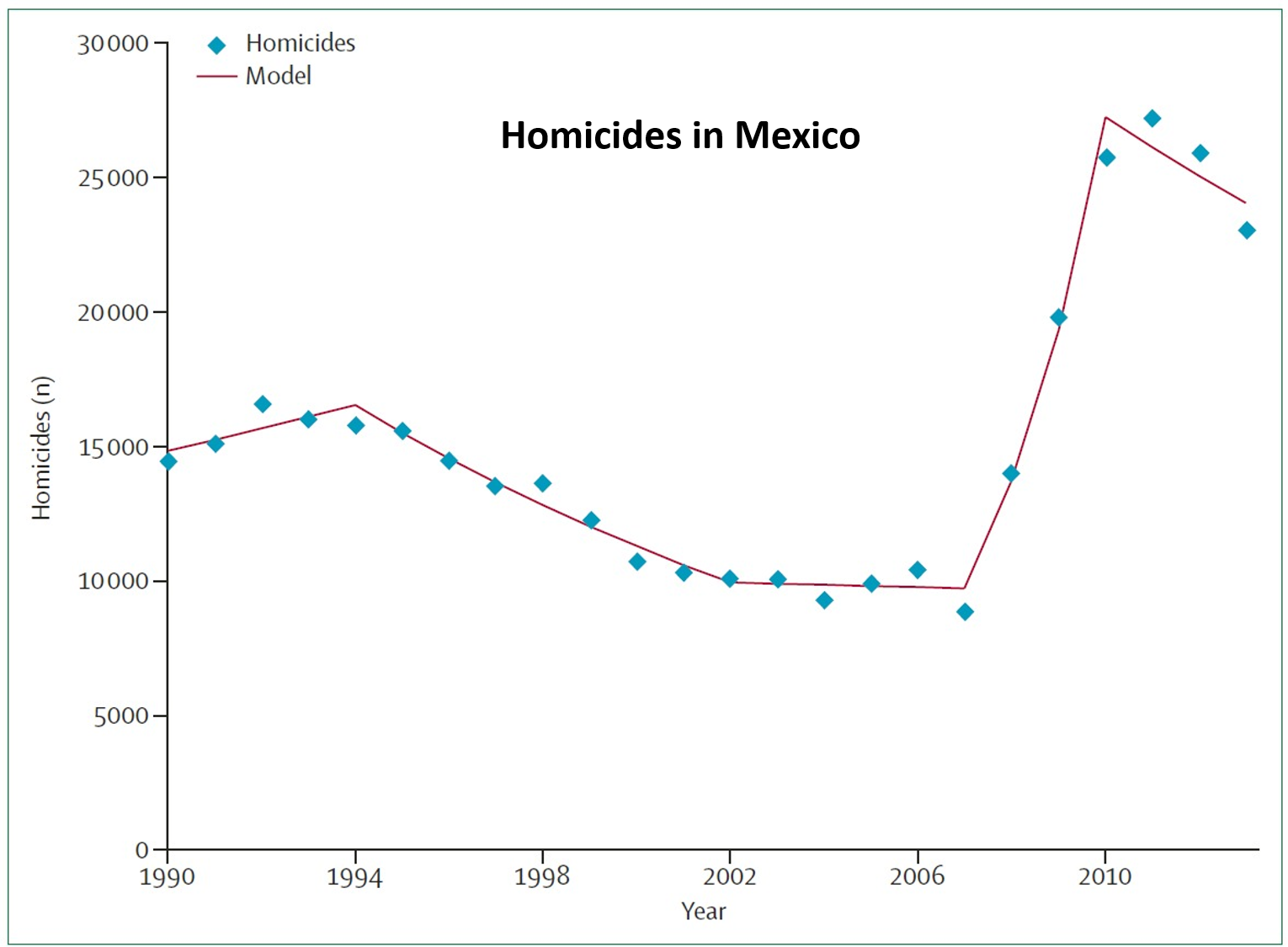

Violence is another familiar product of prohibition, which relies on violence to suppress trafficking and creates black markets in which there is no legal way to resolve disputes. "In Mexico," the report notes, "the striking increase in homicides since the government decided to use military forces against drug traffickers in 2006 has been so great that it reduced life expectancy in the country….The increase in homicides after 2006 is highly significant and notable, especially after a long downward trend in homicides. No other country in Latin America—and few elsewhere in the world—have had such a rapid increase in mortality in so short a time." According to one estimate, "drug-war-related deaths pushed the national homicide rate up by 11 per 100,000," which is "2.5 times the total homicide rate in the USA in 2014."

Some of the damage done by drug prohibition can be ameliorated by harm reduction measures that fall short of legalization, such as needle exchange programs, safe injection spaces, greater availability of the overdose-reversing drug naloxone, and prescription of heroin or other replacement opioids to addicts. The commission recommends those steps, along with decriminalization of possession for personal use, a policy it says has proven successful in Portugal and the Czech Republic. But some problems are inherent in any attempt to forcibly suppress drug use. Although prohibition-related violence can be reduced by dialing back the war on drugs, for instance, it cannot be eliminated as long as production and distribution of certain intoxicants are criminal activities.

"Policies meant to prohibit or greatly suppress drugs present a paradox," the report says. "They are portrayed and defended vigorously by many policy makers as necessary to preserve public health and safety, and yet the evidence suggests that they have contributed directly and indirectly to lethal violence, communicable-disease transmission, discrimination, forced displacement, unnecessary physical pain, and the undermining of people's right to health….We believe that the weight of evidence for the health and other harms of criminal markets and other consequences of prohibition catalogued in this commission is likely to lead more countries (and more US states) to move gradually towards regulated drug markets—a direction we endorse."

Show Comments (30)