Iraq Still Haunts Our Politics

Even in the GOP

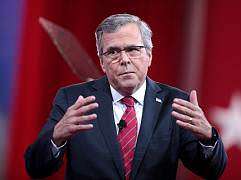

Remember when the Republican foreign policy debate was supposed to consist entirely of hawkish candidates chasing hawkish voters by out-hawking each other? Megyn Kelly shattered that little illusion on Monday when she asked Jeb Bush whether he'd have invaded Iraq in 2003 if he knew then what we know now. Bush said he would, and ever since then rival candidates have been using him for target practice.

It's no surprise that Rand Paul, the closest the Republican field has to a dove, would chide Bush over this, declaring the war a mistake "even at the time." But Ted Cruz, Chris Christie, and John Kasich all said they regretted the war too, even if they weren't willing to take their critique as far as Paul did. Marco Rubio—who was defending the Iraq war as recently as March—now says that not only would he have rejected the war knowing what he knows now, but he's pretty sure George W. Bush would have done the same. Yesterday it all came full circle: Jeb Bush, who claimed on Tuesday that he had misunderstood Kelly's question, announced that with hindsight he "would not have gone into Iraq."

He seemed a little pissy when he said it. This clearly isn't a subject he wants to talk about.

Needless to say, this does not make Cruz or Christie or Rubio, let alone either Bush, a born-again peacenik. The general aim of the candidates' comments isn't to reject the idea of the U.S. as a global policeman; it's to refine it, to say they're willing to use force but will avoid a rerun of the Iraq disaster. At their worst, they sound a bit like Dana Carvey channeling George H.W. Bush on the eve of the first Gulf War:

What's significant is that they're facing the question in the first place—and that they've been pushed to do it not by some famously liberal interviewer but by a host at Fox News.

I grew up in the days of the so-called Vietnam syndrome, when foreign-policy elites fretted that the Indochinese experience had made Americans unwilling to go to war. As late as 1991, the first President Bush—the real one, not Carvey—felt compelled to promise Americans he wasn't leading them into "another Vietnam" as he sent U.S. troops into Iraq. The public's fear of a Saigon rerun certainly didn't keep Washington from intervening around the world. But for the faction that felt the U.S. was insufficiently active abroad—and even in the Reagan years, you could find such people—that fear was still an intolerable imposition. Here they were with exciting new crusades to embark upon, and people kept bringing up the problems with the last one.

So it is today, with Baghdad in the Saigon role. Bush and Rubio would rather be rattling their swords at ISIS or Moscow or somesuch, but the ghosts of the last war keep coming back at inopportune moments. Lurking. Haunting. As though they might have something to tell us.

Show Comments (49)