Can Democrats and Republicans Now Agree to Reform the Awful U.S. Criminal Justice System?

"Tough on crime" laws are bad policy and bad politics.

By the time Mandy Martinson showed up for sentencing, she had managed to not only kick her meth addiction but also regain the dental hygienist job she had lost to it. In 2003, Martinson had moved in with a boyfriend who sold meth and marijuana—and got swept up when federal prosecutors went after him. At her sentencing (for possession, conspiracy to distribute, and possession of a firearm during a "drug-trafficking crime"), the judge noted that "the court does not have any particular concern that Ms. Martinson will commit crimes in the future." But due to mandatory minimum sentencing statutes, he had no choice but to give Martinson a full 15 years in federal prison.

Martinson's was one of several stories shared yesterday at a Capitol Hill panel on criminal justice policy, where representatives from Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM), Right on Crime, the Charles Koch Institute (CKI), the Heritage Foundation, and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) gathered to discuss "the future of bipartisan sentencing and prison reform." It's an area that many are hoping could gain real momentum in what's predicted to be an otherwise gridlocked Congress.

Criminal justice reform is "one of perhaps the only bipartisan issues left in D.C.," Molly Gill, government affairs counsel with FAMM, told the panel.

Something for Everybody

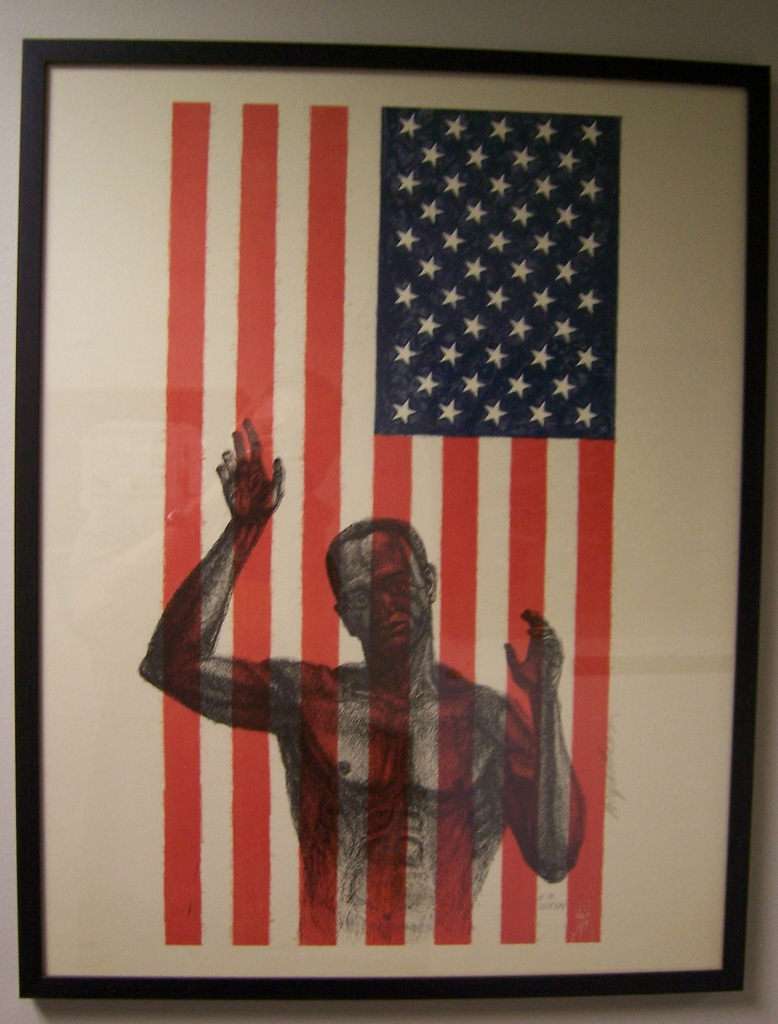

Part of the issue's popularity stems from the way it can capture the passions of disparate constituencies. For the budget cutter? Putting less nonviolent offenders in prison, for shorter times, will be cheaper for the Department of Justice (DOJ) and state prison systems. For the bleeding hearts? It will let people like Martinson have a shot at redemption. For the social-justice inclined? It will help lessen the impact of racially biased criminal-justice policy and practice. For those opposed to the federalization of criminal law? It returns more power to the state and local level. For those concerned with public safety? Getting less "tough on crime" seems to help curb crime.

That last bit was illustrated nicely this week by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which found that the nationwide trend in declining crime rates was greatest in states that also reduced imprisonment rates. "Focusing on criminal justice reform is not a call to go soft on crime," as William Ruger, vice president for research and policy at CKI, stressed at the sentencing reform panel. Rather, it is a call to get smarter about crime.

Perhaps that should go without saying, but until recently most conservative leaders were quick to paint any opposition to criminalizing louder faster harder as a namby-pamby liberal fallacy. Liberals, meanwhile, were busy passing prison-expanding legislation like the 1994 Crime Bill, sponsored by then-Senator Joe Biden and signed into law by Bill Clinton. Part of its legacy was enticing states to enact stricter, more punitive sentencing laws.

That same year, California enacted a "three strikes law", requiring certain offenders receive a mandatory 25-year to life sentence for any third felony conviction. Other states soon followed suit, and 28 now mandate enhanced sentencing for repeat offenders.

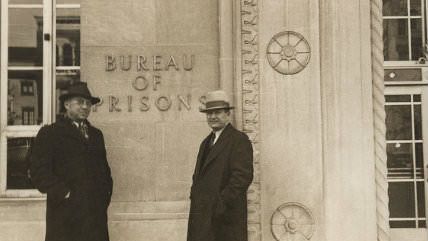

Mandatory Minimums Transformed

Prior to the mid-20th century, mandatory minimum penalties in the U.S. were traditionally relegated to offenses concerning treason, murder, rape, piracy, slave trafficking, and counterfeiting. But the Boggs Act of 1951 (passed with a Democratic president and majority in both houses of Congress) made first-time cannabis, cocaine, or heroin possession an offense with a mandatory minimum sentence of two years in prison.

Under President Richard Nixon, Congress passed the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act, which repealed nearly all mandatory minimum penalties for drug offenses as a way to establish "a more realistic, more flexible, and thus more effective system of punishment and deterrence of violations of the federal narcotics laws." But minimums for drug offenses were reintroduced under President Ronald Reagan, with the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. This law was especially hard on crack cocaine, creating a five-year mandatory sentence for first-time trafficking offenses involving just 5 grams, or about 10 doses ("that's the same as the penalty for 500 grams or more of cocaine powder, which amounts to thousands of doses," Jacob Sullum notes.)

Throughout the '80s and '90s, Congress continued to ratchet up minimum sentences for various drug- and firearm-related offenses. At the same time, America's prison population skyrocketed. Between 1986 and 2013, the number of inmates in state prisons jumped by around 170 percent and the number imprisoned federally by 386 percent.

"Today, the recognition that we need to recalibrate our over-reliance on incarceration is both bipartisan and almost conventional thinking," Nicholas Turner, president of the Vera Institute for Justice, said.

What spurred the change? Reality can't hurt. Violent crime and theft rates have dropped significantly over the past several years. An army of crack babies didn't materialize. Meanwhile mass opinion on drug criminalization, particularly marijuana criminalization, is changing. And there's no doubt that the drug war, mandatory minimums, and other aspects of tough-on-crime policy have ravaged low-income communities. Addressing overcriminalization and overincarceration isn't just right, it's politically feasible at this point in time.

Perhaps even politically popular. A 2014 Reason-Rupe poll found 77 percent support for ending mandatory minimums for all non-violent offenders (up 6 percent since the question was asked last December).

Perhaps even necessary. Many states that have instituted sentencing reforms have done so facing their own skyrocketing and already unsustainable prison costs. The true consequences of crime policy started getting real when state budgets started getting smaller.

States Lead the Way

Between 2009 and 2013, 30 states passed legislation related to how they define and enforce drug offenses, according to Vera. Seventeen states scaled back or otherwise limited mandatory minimum penalties for drug offences. Others expanded community-based sentencing options or passed laws aimed at lessening civic harms for drug offenders upon release.

Some of the best reforms "are coming out of red states," said Gill at yesterday's panel. This probably isn't a coincidence. GOP governors and legislators needed to cut state spending somehow, and keeping non-violent offenders locked up for exorbitant time periods turns out to be a really expensive proposition. According to the Vera Institute, incarcerating someone in state prison costs an average of $31,307 per year, and in some states as much as $50,000-$60,000.

Since the early 2000s, Texas has made a series of reforms—including requiring all drug possession offenses less than a gram get probation instead of jail time and strengthening prison alternatives for juvenile offenders—that have cut the prison population and saved the state billions, all while serious property, violent, and sex crimes have declined. Georgia passed a series of reforms in 2011-2013. Since then, the proportion of violent and sex offenders in Georgia prisons increased from 58 percent in January 2009 to 64 percent in June of 2013—a sign that the legislation's intended goal of "focusing expensive prison space on dangerous offenders while using more cost-effective, community-based sanctions for less serious lawbreakers" is working.

California voters this month passed Prop. 47, which converted simple drug possession offenses and other low-level felonies to misdemeanors. It earned the support of prominent Democrats, Republicans (including Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul), religious groups, the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, the ACLU, and celebrities such as Cameron Diaz and Jay-Z.

State criminal-justice reform successes have emboldened lawmakers in D.C., said Laura Murphy, director of the D.C. legislative office for the ACLU, at yesterday's panel. Right now a coalition on the left and right has rallied around the Smarter Sentencing Act, which would cut mandatory minimums for certain federal drug crimes in half, among other mostly good reforms. The proposal was introduced in the Senate by Sens. Richard Durbin (D-Texas) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) and in the House by Reps. Raul Labrador (R-Idaho) and Bobby Scott (D-Va.), is co-sponsored by 85 legislators, and has the support of groups from the United Methodist Church to the NAACP to the American Bar Association and the American Correctional Association. Grover Norquist is also a fan.

Another bill gaining traction is the Recidivism Reduction and Public Safety Act of 2014, which would allow greater sentence reductions for good behavior. It passed the Senate Judiary Committee with bipartisan support in March 2014.

Why Now?

Can prison and sentencing reform really become popular Congressional causes? The timing seems right. We've got ample legislators looking to distinguish themselves in 2015—without compromising in any critical ideological area. Nobody's about to work together on health care reform or even school lunch policy.

Criminal justice reform, in contrast, is currently something of a political blank slate—an issue still waiting for the ruling parties to imprint their 21st century narratives upon it. Absent the toxicity that comes with foregone ideological absolutes, criminal justice legislation holds hordes of potential for politicians looking to be seen as ideas people or show skill at "reaching across the aisle."

Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), who introduced the reentry-minded REDEEM Act with Sen. Rand Paul in July, told Huffington Post that he's "gotten really good signs" from his colleagues that criminal justice reform "is something there is a commitment to do." Booker is also "pretty confident" this is an issue soon-to-be Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell "wants to lead on."

Seasoned politicians like McConnell don't generally "want to lead on" issues out of the goodness of their hearts—they want to do so when an idea has potential and momentum. And this makes me hopeful. Ambition is a much better motivator than altruism when it comes to getting things done in politics. Bring on the criminal justice reform zeitgeist? As Right on Crime director Marc Levin said yesterday, "This is good policy but it's also nice that this is good politics."

Show Comments (33)