Britain's Dream of an E.U. Exit is Slowly Turning Into Nightmarish Reality

Wednesday's debate highlights the significance of euroskepticism in British politics

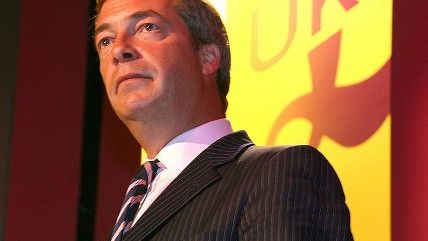

The British wish to leave the European Union for good has never been clearer after Wednesday's televised debate, the second between pro-European Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg and arch-euroskeptic Nigel Farage. Such a breakaway might seem like a good idea for libertarian Brits—but whether it would really be such a smart move is far from clear.

Unlike in the U.S., televised debates are a rarity in Britain and—it might seem impossible to believe this—still retain an air of glamor and excitement. They really matter. So when just 27 percent of voters judge Clegg to have performed best, compared to 68 percent for Farage, you can get a strong sense of the scale of Wednesday's victory.

With important European elections now less than two months away, there is a strong possibility that Farage's United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) might actually emerge as the outright winners. That would send shivers down the spine of those following the debates in Brussels and beyond. But it now seems like a real probability.

The rest of the world should wake up to the fact that, after years of rhetoric, the great dream of the U.K.'s potential exit from the E.U. is now a political nightmare slowly coming true. It has been simmering away, troubling but never alarmingly so, for years. Only now, after these two televised debates, is British euroskepticism suddenly threatening to boil over.

Everyone needs to get used to the fact, and fast. It ultimately means we could finally see a straightforward in-or-out referendum on Britain's ongoing membership of the E.U. before the end of the decade. Mainstream politicians' efforts to avoid a referendum on the issue can only be sustained for so long—and resentment has only built up as a result.

That resentment is the fuel that is helping burn UKIP's flame. For a party that's never won a seat in the House of Commons at a general election, it's got a lot going for it right now. For many disgruntled voters fed up with the mainstream, UKIP is the new protest vote—especially now that Clegg's Liberal Democrats stuck in government as the coalition's junior party. The rise of right-wing politics in Britain has helped UKIP prey on fears and misconceptions about immigration, too. And it's proved adept at rustling up the sort of nostalgic jingoism that moves Union Jack-waving Grannies into a fervour of tearful patriotism. The British are a reserved bunch at the best of times, but UKIP makes its supporters feel like there's more to this country than just the faded glories of an ex-Empire.

UKIP is, in its own words, a "libertarian" party. It doesn't really mean it in the true sense of the word. No party that supports the continued existence of the National Health Service really could. Even in the context of British politics, though, its opposition to statist solutions seems a little dubious. This is the party, after all, that proposed banning the burka. It didn't much like the idea of gay marriage. And its leader, Farage, came under fire on Wednesday for admitting the one politician he admires in the world right now is Vladimir Putin—not a leader exactly known for his libertarian values.

"If you scratch the surface you find one of the most illiberal and intolerant political parties in the U.K.," says Martin Horwood, the foreign affairs spokesperson for Clegg's Liberal Democrats. "The idea they are champions of personal freedom doesn't really stand much scrutiny."

He points out that Europe has provided individuals with a lot of safeguards for individual liberty, whether over consumer rights like data protection or the right to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

"Those who take the most liberal position on freedom of movement and free trade are quite clear that the European Union is the way to deliver that on a large scale," Horwood adds. "At its heart, UKIP and those campaigning for exit from the European Union are Little Englanders who would opt for protectionist policies at the drop of a hat."

The problem for those defending the status quo is that it's actually very hard to work out what would happen if Britain walked away from Europe. Imagining what it would be like negotiating a trade deal with the E.U. from outside isn't an argument that can be based on hard, cold figures. A lot of this is about gut feel—which is why those looking for a change for the hell of it are doing so well in the polls.

"It's not necessarily clear there's a straightforward liberty gain from leaving the E.U.," says Stephen Davies, Director of Education at the free market Institute of Economic Affairs think tank. He doesn't even think there's much of a link between euroskepticism and libertarianism, either. "They tend to go together because of a commitment to a particular style of politics more than anything else… I don't think there's a well-thought out necessarily logical connection."

Davies' theory is that the European project has become firmly left-wing and is now viewed through a very partisan lens. It wasn't always this way; in the 1970s socialists desperately wanted to leave Europe in order to set up a command economy. That all changed, though, when the left realised expanding European control could actually increase its influence. Shut out of power in the 1980s, the left saw it as a way of getting policies adopted that it couldn't pass domestically. Right-wingers' views of Europe have been slowly shaped against it as a result.

Now we're seeing the consequences of these frustrations—and they're getting very ugly indeed. We don't need to wait until May 22nd, when the European elections take place in Britain, to find out what all this means for the U.K. Right now those arguing against a British exit are losing, and losing badly. Clegg has done nothing to boost the pro-European cause with these debates. Farage, by contrast, has made the most of this opportunity to preach his message of jingoistic fervour to a big audience. There may not be much to back up his claims to libertarian politics—but when it comes to the raw emotions of the European debate, does he really care?

Show Comments (342)