James Comey Has Craptacular Opinions on Mass Incarceration and Prosecutors

The former top G-Man thinks "mass incarceration" is a misnomer and that taking Martha Stewart down was pretty much the work of God.

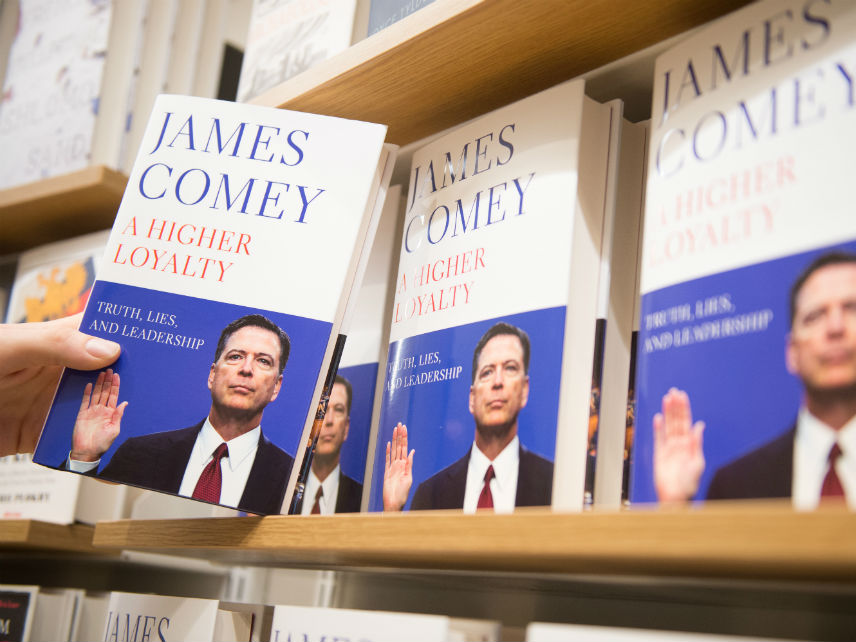

Former FBI chief James Comey has been storming the airwaves this week to promote A Higher Loyalty, his very-sincere-and-definitely-not-an-attempt-to-burnish-his-reputation-and-cash-in-on-getting-fired-by-the-president memoir.

While much of the buzz around the book involves its comments on Donald Trump, Comey is a career lawman, which means A Higher Loyalty also filled with spicy takes on criminal justice, paeans to the rule of law, and sweaty odes to the great and powerful institutions that save us from anarchy.

Over on Twitter, freelance writer Patrick Blanchfield has been reading through Comey's new book and flagging particularly dumb passages about criminal justice. He's been busy.

For example, here is Comey recalling a meeting he had with Barack Obama, where he explained to the president that the term "mass incarceration" is really quite mean to police and prosecutors:

Although I agreed that the jailing of so many black men was a tragedy, I also shared how a term he used, "mass incarceration"—to describe what, in his view, was a national epidemic of locking up too many people—struck the ears of those of us who had dedicated much of our lives to trying to reduce crime in minority neighborhoods….I thought the term was both inaccurate and insulting to a lot of good people in law enforcement who cared deeply about helping people trapped in dangerous neighborhoods. It was inaccurate in the sense that there was nothing "mass" about the incarceration: every defendant was charged individually, represented individually by counsel, convicted by a court individually, reviewed on appeal individually, and incarcerated. That added up to a lot of people in jail, but there was nothing "mass" about it, I said. And the insulting part, I explained, was the way it cast as illegitimate the efforts by cops, agents, and prosecutors—joined by the black community—to rescue hard-hit neighborhoods.

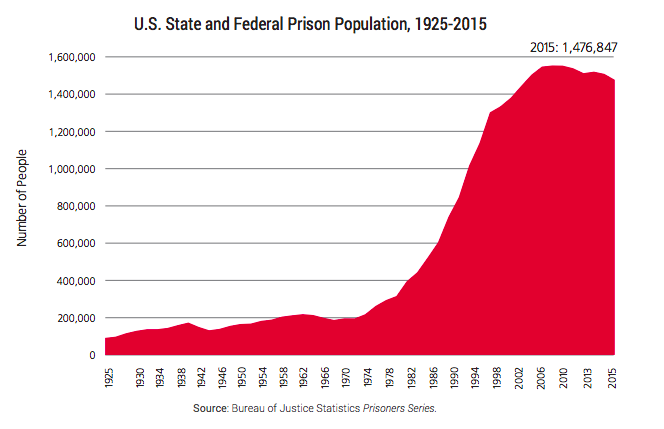

"Mass incarceration" may be a slippery term, but it strains credulity to argue there's nothing "mass" about a 500 percent rise in the U.S. prison population over 40 years. This historically unprecedented warehousing of human beings wasn't an accident or something the country just stumbled into. It was a result of deliberate policies by state and federal officials, a shift to what Berkeley law professor Jonathan Simon calls "total incapacitation."

To put this in some perspective, California had 20,000 prisoners in 1977. By 2003, it had 160,000. Between 1980 and 2000, the Golden State built 20 new prisons to house inmates created by its punitive laws.

Here's what that rise looked like nationally:

And while Comey is correct that defendants are sentenced individually, not collectively, there's nothing individual about the mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines that lawmakers passed to fill all those new prisons.

Such guidelines take away a judge's ability to weigh defendants' character, circumstances, and future prospects, essentially turning judges into little more than rubber stamps during sentencing hearings. Read Reason's investigation of Florida's mandatory minimum sentencing laws to see judges making comments to just that effect. ("Under this set of circumstances, this court does nothing more than perform an administerial function. I sign the papers. I'm on autopilot.") Mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines also transferred discretion from the judiciary to the prosecutors, who proved to be remarkably aggressive in pursuing criminal charges even as crime rates fell throughout the late '90s and early 2000s.

Claiming the term "mass incarceration" is insulting to law enforcement is an attempt to replace the real target of criminal justice reformers—the policies, institutions, and political imperatives that incentivize and protect bad policing and overzealous prosecutions—with the ostensibly well-meaning frontline of law enforcement, whose feelings must be preserved.

Oh, but Comey isn't done. He also has bad opinions on the rule of law.

Readers might remember that Martha Stewart was sentenced to five months in federal prison in 2004 as a result of an insider trading investigation. The businesswoman and homemaker extraordinaire wasn't actually convicted of securities fraud. The feds could only make the charges of conspiracy, obstruction, and false statements stick.

Because almost everyone intentionally or unintentionally tells falsehoods to the FBI, it's a common tactic for federal prosecutors to ring up defendants on a smorgasbord of charges, confident that they'll at least get a conviction for false statements. Think that's unjust? For Comey, it's nothing less than preserving the fabric of society like an Old Testament God:

The Stewart experience reminded me that the justice system is an honor system. We really can't always tell when people are lying or hiding documents, so when we are able to prove it, we simply must do so as a message to everyone.

There was once a time when most people worried about going to hell if they violated an oath taken in the name of God. That divine deterrence has slipped away from our modern cultures. In its place, people must fear going to jail. they must fear their lives being turned upside down. They must fear their pictures splashed on newspapers and websites. People must fear having their name forever associated with a criminal act if we are to have a nation with a rule of law. Martha Stewart lied, blatantly, in the justice system. To protect the institution of justice, and reinforce a culture of truth-telling, she had to be prosecuted. I am very confident that should the circumstance arise, Martha Stewart would not lie to federal investigators again.

It takes an incredible amount of self-regard to imagine one is doing the work of the Almighty in a fallen world. Luckily, James Comey is up to the job.

Show Comments (135)