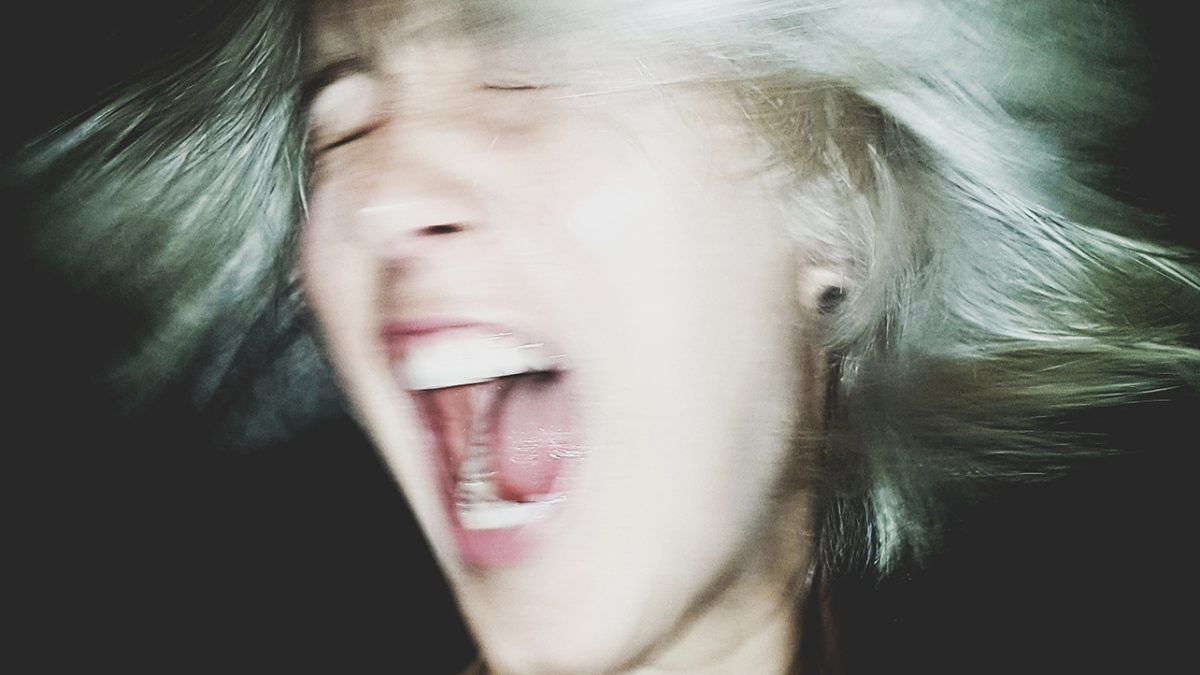

The Future Is Female. And She's Furious.

Is rage the future of feminism?

In October, a few days after Brett Kavanaugh was sworn in as a Supreme Court justice, The Washington Post published one woman's account of channeling her rage into half an hour of screaming at her husband. "I announced that I hate all men and wish all men were dead," wrote retired history professor Victoria Bissell Brown, entirely unapologetic despite conceding that her hapless spouse was "one of the good men."

While Brown's piece was more clickbait than commentary, it was an extreme expression of a larger cultural moment. 'Tis the season to be angry if you're a woman in America—or so we're told.

The storm of sexual assault allegations that nearly derailed Kavanaugh's confirmation was just the latest reported conflagration of female fury. The Kavanaugh drama coincided with the first anniversary of the downfall of the multiply accused Hollywood superpredator Harvey Weinstein. But this decade's wave of feminist anger had been building for several years before that—from the May 2014 #YesAllWomen Twitter hashtag, created to express women's vulnerability to male violence after woman hater Elliot Rodger went on a shooting and stabbing rampage in California, to the November 2016 election, in which the expected victory of America's first woman president was ignominiously thwarted by a man who casually discussed grabbing women's genitals.

While the "female rage" narrative does not represent all or even most women, there is little doubt that it taps into real problems and real frustrations. The quest for women's liberation from their traditional subjection is an essential part of the story of human freedom—and for all the tremendous strides made in the United States during the last half-century, lingering gender-based biases and obstacles remain an unfinished business. But is rage feminism (to coin a phrase) the way forward, or is it a dangerous detour?

The case for rage is made in two new books published almost simultaneously in the fall: Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women's Anger, by activist Soraya Chemaly, and Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger, by New York columnist Rebecca Traister.

Traister's book is, despite its forays into the history of American feminism, very much of the current moment. It is dominated by the 2016 presidential race, the Women's March, and the #MeToo movement. Traister believes that Donald Trump's election woke the "sleeping giant" of female rage at the patriarchy. (Along the way, she seems to suggest that pre-2016 feminism was a mostly "cheerful" kind, with a focus on girl power and sex positivity—an account that airbrushes not only #YesAllWomen but many other days of rage on feminist Twitter and on websites such as Jezebel.) She wants women to hold on to this anger and channel it into a struggle for "revolutionary change," rather than to move on and calm down in deference to social expectations. "Our job is to stay angry…perhaps for a very long time," Traister warns darkly.

Rage Becomes Her provides a broader context for this anger. Chemaly, the creator of that #YesAllWomen hashtag, sets out to count the ways sexist oppression continues, in her view, to permeate the lives of women and girls in America. Her indictment includes inequalities in school and at work, ever-present male violence, rampant and usually unpunished sexual assault, the sidelining of women in literature and film, male-centered sexual norms, subtle or overt hostility toward female power and ambition, and a variety of petty indignities, from "mansplaining" to catcalls to long bathroom lines. Like Traister, Chemaly sees women's long-suppressed anger as a necessary driver of change.

The themes that preoccupy Traister and Chemaly are also explored in an earlier book—Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, by the Cornell philosopher Kate Manne—which was published in late 2017 and has been widely hailed as a new feminist classic. Like Good and Mad, Down Girl views Trump's victory as the triumph of patriarchal backlash; like Rage Becomes Her, it treats Rodger's massacre as a defining moment in American male-female relations. Manne may not issue an explicit call for anger, but the logic of Down Girl is unmistakable: A deeply entrenched misogyny ruthlessly punishes women who refuse to defer to men, and female fury is a natural and salutary response.

You can debate the extent to which gender inequalities in 21st century liberal democracies stem from present-day sexism, from cultural baggage from the past, or from personal choices and innate sex differences at an individual level. But does the gallery of horrors in the literature of feminist rage really reflect women's lives in today's America?

In 1994, dissident feminist Christina Hoff Sommers published a controversial book, Who Stole Feminism?, that charged feminist activists and authors with using bogus facts and other "myth-information" to portray modern Western women as brutally oppressed. Much of this critique has held up—and, as the new crop of feminist books shows, has remained relevant.

Indeed, one pseudo-fact debunked by Sommers and mostly retracted by its authors, school equity crusaders David Sadker and the late Myra Sadker, makes a comeback in Chemaly's book: the claim that boys in class call out answers eight times as often as girls do, while girls who speak out of turn are usually rebuked. Manne not only recycles that "fictoid" (as Sommers called it) but garbles it.

These are no isolated lapses. A cursory fact check of Chemaly's lengthy endnotes reveals that many of her sources don't say what she claims they do. The claim that "when women speak 30 percent of the time in mixed-gender conversations, listeners think they dominate," for instance, is sourced to a 1990 study that shows only a slight tendency to overestimate the female portion of a male-female dialogue. (Chemaly's claim is apparently derived from a passing mention in the study of a 1979 article by Australian radical feminist scholar Dale Spender.) The purported source for another alleged fact—"domestic violence injures more American women annually than rapes, car accidents and muggings combined"—is a book appendix by journalist Philip Cook that debunks this very myth.

Three new books suggest that a deeply entrenched misogyny ruthlessly punishes women who refuse to defer to men, and that female fury is a natural and salutary response.

Chemaly's treatment of news stories is just as cavalier. For example, she claims that Michigan Circuit Court Judge Rosemarie Aquilina was criticized for showing "clear contempt" toward former sports doctor and confessed sexual abuser Larry Nassar at his sentencing, supposedly due to "deep unease with women passing judgment on men." In fact, Aquilina was widely praised as a champion for victims. The criticism had to do with her suggestion that Nassar deserved punishment by rape.

Beyond the fictoids, what is the bigger picture? Manne defines misogyny so broadly—as a "systemic" bias that threatens women with "hostile consequences" for violating patriarchal norms, especially the expectation that women will be "givers" who tend to male needs—that any antagonism toward any woman for almost any reason can fit the label.

According to Manne, "misogyny is killing women and girls, literally and metaphorically." Deadly misogyny is exemplified here by Rodger (a severely disturbed man who killed two women and four men and planned to cap a sorority massacre with indiscriminate slaughter in the streets), but also by more ordinary domestic killings. Manne also asserts that men who victimize women get disproportionate sympathy, a.k.a. "himpathy" (a word to join mansplaining on the list of atrocious feminist neologisms).

Down Girl never grapples with issues that complicate its narrative: the ways men have been traditionally expected to "give" and sacrifice for others' needs in war and breadwinning; the fact that the primary victims of male violence are other males; the reality of domestic abuse in same-sex couples and intimate violence by women; the evidence that violent crimes with female victims tend to be punished more severely while female perpetrators tend to be treated more leniently.

Nor is Manne a particularly reliable narrator. At one point, she quotes excerpts from a news story in which a woman's family refuses to blame the boyfriend who fatally stabbed her and was later shot dead by police. But she leaves out a key detail: The woman was apparently unstable and prone to violence, and the man had likely acted in self-defense.

In all three books, the 2016 election looms large as an odious testament to the enduring power of patriarchy and misogyny. Yet you can loathe Trump and still question the assumption that Hillary Clinton's loss was the result of sexism. Some anti-Clinton sentiment certainly had to do with her gender; then again, so did what enthusiasm her campaign managed to generate. Traister, Chemaly, and Manne lament the stereotypes and double standards faced by ambitious and powerful women. Yet they never mention recent research by scholars such as Deborah Jordan Brooks of Dartmouth College or Jennifer Lawless of American University, who looked at actual political campaigns in the last decade and concluded that female candidates were not held back by voter biases.

The central theme of the call to feminist rage is sexual victimhood: #MeToo and the crusade against American "rape culture" that began a few years earlier. Few would doubt the worthiness of the cause. The scandals that followed Weinstein's exposure included story after story in which powerful men seemed to regard the women in their professional orbit as a personal harem and in which women's attempts to complain were deep-sixed; many of these stories, backed by contemporaneous reports to colleagues, friends, or family, involved allegations of criminal conduct ranging from sexual assault to indecent exposure. Even critics of feminist sex panic, such as Sommers and Northwestern University film studies professor Laura Kipnis, were mostly on board with #MeToo.

But from the start, the anti-patriarchal revolt had its own complications. For one, while revelations of male victims (and, eventually, female abusers) do not negate the claim that sexual harassment is linked to male power over women, these incidents do suggest that sexism is not the only reason high-status predators have had license to abuse. What's more, some career-killing accusations involved clumsy but noncoercive come-ons, awkward compliments, off-color jokes, or even vaguer offenses. Veteran National Public Radio host Leonard Lopate was fired over "inappropriate" comments such as telling a female producer working on a cookbook segment that avocado was derived from the Aztec word for testicle. Vince Ingenito, former editor of the pop culture website IGN, was accused of harassing a female staffer and onetime friend by complimenting her looks, disparaging some men she dated, and once telling her that he wished he could "go all night" as he'd done at her age.

When comedian Aziz Ansari got #MeTooed for being a jerk on a date, many supporters of the movement felt it had gone too far. But not Chemaly, who insists that the resulting "conversation" was needed to challenge "the tremendous power…that men can wield over women" in intimate encounters, even when no institutional power is involved. For both Chemaly and Traister, sexuality in the workplace is virtually always a male imposition on women, and male-female sexual dynamics under any circumstances are steeped in male "entitlement" and privilege. In this paradigm, female agency is virtually nonexistent.

Perhaps the most revealing part of Good and Mad is Traister's elegy for the late radical feminist writer/activist Andrea Dworkin, whom she sees as a tragic, misunderstood, maligned prophet of #MeToo: She speaks of "the sorrow I felt that Dworkin was not here to see what was happening." While she admits that Dworkin's anti-porn crusade was misguided, Traister defends her larger vision and her relentless fury while sanitizing her more outré views. (Traister insists that "all sex is rape" is a misreading of Dworkin's Intercourse, even though the book clearly equates penetrative sex with female subjugation and violation: "There is never a real privacy of the body that can coexist with intercourse.…The thrusting is persistent invasion.…She is occupied—physically, internally, in her privacy.")

Traister's tribute to Dworkin is a whitewash, but she's not wrong about the current feminist revival as a Dworkin moment. Many of the ideas championed by Dworkin and her sister in arms, legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon, since the 1970s—that the lives of modern Western women and girls are an everyday "atrocity" of male depredations; that feminism, in MacKinnon's words, "is built on believing women's accounts of sexual use and abuse by men"; that bad speech constitutes "harm"—are now mainstream feminist beliefs.

That does not bode well for feminism.

In many ways, 20th century American feminism was one of liberal democracy's great success stories. Overtly discriminatory laws and policies crumbled; cultural attitudes on a wide range of subjects underwent a dramatic shift. (By 2000, more than nine out of 10 Americans said they would vote for a female presidential candidate, up from about one in two in 1955.) For some, this means that feminism has won its battle. For others, that it must now fight subtler and more complicated obstacles.

Even in the generations raised with the norm of gender equality, it's still mostly men who occupy positions of power and mostly women who tend to home and children. Conservatives and many libertarians see this as the result of free choices and differing preferences; most feminists blame structural sexism and deep-seated, often unconscious prejudices. While feminist arguments often rely on far-reaching speculation, feminism's critics can be too dismissive of the role played by cultural biases, social pressures, and similar factors in hindering equal opportunity. For example, several studies of employee performance reviews, most recently by Harvard researcher Paola Cecchi Dimeglio, have found that women tend to get less constructive feedback and more personal criticism, especially for being "too aggressive."

Addressing these issues is a legitimate goal, and one that doesn't require state coercion. In recent years, social media have given activists highly effective tools allowing them to use public opinion and consumer power to work for change without getting the government involved—whether it's to hold corporations accountable for condoning sexual predation in the workplace, to call for children's products that don't treat adventure and invention as the sole preserve of boys, or to push for more gender balance in various projects from films to academic conferences.

Unfortunately, when grievances become wildly inflated and the default mode for activism is rage, advocacy can easily turn into a baneful hypervigilance (do women really gain when every conversation is zealously monitored for "microaggressions" or "manterruptions"?) and misfocused mob outrage. Take the trashing of renowned British biochemist Tim Hunt in 2015 over alleged sexist remarks about the trouble with "girls in the lab." Hunt was roundly reviled as a misogynist on social media and in the press, then stripped of several posts. That fate came despite objections from attendees who said his offense was a misreported self-deprecating joke—a claim later supported by a partial audio recording—and despite his undisputed record as a champion of women in science.

Modern feminism, with its framework of male privilege and female oppression, takes a simplistic and one-sided view of gender dynamics in modern Western societies. It ignores the possibility that some gender-based biases (such as the expectation that males will perform physically grueling and/or dangerous tasks, paid or not) may benefit women or disadvantage men. It disregards the vast diversity and flexibility of cultural norms. It refuses to recognize that there is no perfect solution to the problem of dispensing justice when someone alleges a crime with no witnesses and both parties tell a credible story.

Rage-driven activism can be particularly destructive when it targets and politicizes interpersonal relationships, an area in which the sexes are probably equal but different in bad behavior. Victoria Bissell Brown's verbal abuse of her husband is hardly a typical example, but even Traister sees nothing wrong with the fact that, at the height of #MeToo, her husband once marveled, "How can you even want to have sex with me at this point?"

Anger can be productive, usually as an impetus for short-term action. But rage feminism is a path of fear and hate. It traps women in victimhood and bitterness. It demonizes men, even turning empathy for a male into a fault, and dismisses dissenting women as man-pleasing collaborators. It short-circuits important conversation on gender issues.

Urging women to disregard warnings about the perils of rage, Traister writes, "Consider that the white men in the Rust Belt are rarely told that their anger is bad for them." But aren't they? The anger of "white men in the Rust Belt" is commonly portrayed as an unfocused, dangerous emotion that scapegoats innocents and empowers unprincipled demagogues like Trump. The anger of privileged women is not much of an improvement.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Future Is Female. And She's Furious.."

Show Comments (464)