The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent | Est. 2002

SCOTUS Puts Skrmetti SDP Case Out Of Its Misery

The ACLU's cert petition is denied, and several other petitions are GVR'd.

Last week I speculated what would happen to the ACLU's cert petition in Skrmetti that raised the Due Process issue. I wondered if the Court would GVR the parental rights issue in light of Mahmoud.

Today's order list denied review in L.W. v. Skrmetti. There were no recorded dissents. It seems the Due Process claim is now dead. The Tennessee law, and others like it, will now go into effect.

Indeed, the Court GVR'd several related cases. First, West Virginia excluded treatment for gender dysphoria from Medicaid. The Fourth Circuit held this exclusion violated the Equal Protection Clause. Second, North Carolina excluded treatment for gender dysphoria from the state employee health plan. The Fourth Circuit likewise ruled against the state. Third, Idaho denied Medicaid coverage for sex-reassignment surgery. After Skrmetti was argued, the Ninth Circuit found this ruling was unlawful.

These issues will bubble back to the Court in a year or so. Let's see if the Fourth Circuit can see the writing on the wall. Speaking of which, guess which Circuit was the "Biggest Loser" at the Court this term? No, it was not my beloved Fifth Circuit.

David Lat explains (based on Adam Feldman's Stat Pack):

Some circuits got reversed a lot. Subjectively and anecdotally, it felt to me that the Fifth Circuit took it on the chin this Term in terms of reversals. But if you look at reversals in percentage terms, the First, Fourth, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits were the most reversed, all with a 100 percent reversal rate—based on two, eight, four, and five cases decided by SCOTUS, respectively. So with a 0-8 record before the justices, the Fourth Circuit was the "biggest loser," in terms of the court with the highest reversal rate and the highest total number of cases. (The Ninth Circuit had three cases that were dismissed as improvidently granted.)

The Fifth Circuit didn't do that badly. The Fifth Circuit had the most total cases reversed (10), and some were high-profile—such as Bondi v. VanDerStock (a statutory-interpretation case about "ghost guns"), Kennedy v. Braidwood Management (an Appointments Clause challenge to an Affordable Care Act-created task force), and FCC v. Consumers Research (a nondelegation challenge to the FCC's "universal service" scheme). But the Fifth Circuit wound up with a 77 percent overall reversal rate, since it was also affirmed in three appeals—including the closely followed Free Speech Coalition, Inc. v. Paxton (a First Amendment challenge to an age restriction for pornography websites).

I think the reversal rate should include GVRs as well.

Stay tuned for more.

So What'd I Miss?

I apologize for my blog silence the past five days. I have just finished work on a major book deadline (much more about that soon), so was unable to opine on the Court's final decisions. I have some thoughts. So stay tuned.

The Supreme Court, Martians, Justice Jackson, and Chief Justice Roberts

Justice Jackson's dissent in the universal injunction case (CASA, Inc. v. Trump) includes this line:

A Martian arriving here from another planet would see these circumstances and surely wonder: "what good is the Constitution, then?" What, really, is this system for protecting people's rights if it amounts to this—placing the onus on the victims to invoke the law's protection, and rendering the very institution that has the singular function of ensuring compliance with the Constitution powerless to prevent the Government from violating it? "Those things Americans call constitutional rights seem hardly worth the paper they are written on!"

Some people have suggested there's something strange or inappropriate about bringing Martians into it, but it seems a pretty familiar locution. Here, for instance, is Chief Justice Roberts from Riley v. California (2014), which labels it familiar enough to be "proverbial":

These cases require us to decide how the search incident to arrest doctrine applies to modern cell phones, which are now such a pervasive and insistent part of daily life that the proverbial visitor from Mars might conclude they were an important feature of human anatomy.

Justice Thomas used a similar phrase in Foster v. Chatman (2016) and Justice O'Connor in Engle v. Isaac (1982), both quoting Judge Henry Friendly, Is Innocence Irrelevant? Collateral Attack on Criminal Judgments, 38 U. Chi. L. Rev. 142, 145 (1970):

No Qualified Immunity for School District Police Officer Who Seized Home-Schooled 14-Year-Old from Home

The child, and her 12-year-old brother, were left under the supervision of a neighbor by the mother, who left town for six days for a foreign job interview.

From McMurry v. Weaver, decided Friday by the Fifth Circuit (Judge Carolyn Dineen King, joined by Judge Jim Ho and Irma Carrillo Ramirez):

In October 2018, Plaintiff-Appellee Megan McMurry resided in a gated apartment complex in Midland, Texas with her daughter, Plaintiff-Appellee J.M., (then age fourteen) and son C.M. (then age twelve). J.M. took classes virtually from home, C.M. attended Abell Junior High School (Abell), part of the Midland Independent School District (MISD), and Ms. McMurry taught at Abell. Ms. McMurry's husband and the children's father, Plaintiff-Appellee Seth Adam McMurry, was deployed to the Middle East with the National Guard. To explore a job opportunity that would allow the family to move closer to Mr. McMurry, Ms. McMurry planned a trip to Kuwait from Thursday, October 25 to Tuesday, October 30.

Before leaving, Ms. McMurry arranged for a neighbor, Vanessa Vallejos, to check in on J.M. and C.M., and for coworkers to take C.M. to school. J.M. often babysat Ms. Vallejos's son, and Ms. McMurry had arranged for Ms. Vallejos to watch J.M. and C.M. while she was out of town in the past.

On the morning of October 26, 2018, Defendant-Appellant Alexandra Weaver, a police officer with MISD, received a text from a counselor who was supposed to take C.M. to school that day. Weaver already knew that Ms. McMurry was out of the country because Ms. McMurry had emailed all Abell campus employees including Weaver a few days earlier. Upon receiving the text, she became concerned that J.M. and C.M. were without adult supervision, and informed her supervisor, Officer Kevin Brunner, of her concerns.

Weaver and Brunner then proceeded to meet with three of Ms. McMurry's coworkers and learned that (1) Ms. McMurry was traveling for a job interview; (2) C.M. was at school; (3) a neighbor, whose son J.M. often babysat, was checking on the children daily; and (4) J.M. was homeschooled. Weaver and Brunner then went to the McMurrys' apartment to conduct a welfare check on J.M.

Parental Rights and Youth Gender Medicine

The Supreme Court just declined this morning to consider this issue, but here's how a noted lower court judge analyzed the matter.

Some people have asked: Why aren't state statutes limiting youth gender medicine treatments violations of parental rights (given that they apply even when the parents ask for the treatment for their children)? The answer, I think, is that the Court hasn't generally recognized a constitutional right to get forbidden medical procedures for oneself, much less a right to get them for one's children. I think Sixth Circuit Judge Jeffrey Sutton correctly summarized the legal rules in L.W. v. Skrmetti (which the Supreme Court just declined to review):

There is a long tradition of permitting state governments to regulate medical treatments for adults and children. So long as a federal statute does not stand in the way and so long as an enumerated constitutional guarantee does not apply, the States may regulate or ban medical technologies they deem unsafe.

Washington v. Glucksberg puts a face on these points…. The Court reasoned that there was no "deeply rooted" tradition of permitting individuals or their doctors to override contrary state medical laws. The right to refuse medical treatment in some settings, it reasoned, cannot be "transmuted" into a right to obtain treatment, even if both involved "personal and profound" decisions….

Abigail Alliance hews to this path. The claimant was a public interest group that maintained that terminally ill patients had a constitutional right to use experimental drugs that the FDA had not yet deemed safe and effective. As these "terminally ill patients and their supporters" saw it, the Constitution gave them the right to use experimental drugs in the face of a grim health prognosis. How, they claimed, could the FDA override the liberty of a patient and doctor to make the cost-benefit analysis of using a drug for themselves given the stark odds of survival the patient already faced? In a thoughtful en banc decision, the D.C. Circuit rejected the claim. The decision invoked our country's long history of regulating drugs and medical treatments, concluding that substantive due process has no role to play….

Liability for Suicide When Student Is Upset by Misconduct Investigation, and Resulting "Community Pressure"

In a decision June 20 in Bruno v. Mills, R.I. Superior Court Judge Richard Licht affirmed a verdict in favor of plaintiff, whose 15-year-old son Nathan committed suicide as a result of an investigation at school. The investigation started with the son's prank calls to a teacher (Mr. Moniz) and then led into an attempt to pressure the son into disclosing the names of two accomplices. The opinion is over 26,000 words long, so here's just a very short excerpt. I'm particularly interested in what this means more generally for investigations, whether at high schools, in college, or even in law schools—for instance, investigations into alleged sexual misconduct, racist comments, plagiarism, other cheating, and more:

[W]hether sufficient evidence was presented that Mr. Moniz breached a standard of care as to Nathan in large part depends on the substance of Dr. Leonard's testimony…. Dr. Leonard adequately explained the duties and conduct expected of school personnel and addressed how Mr. Moniz's specific conduct constituted a breach thereof.

To start, Dr. Leonard explained that when a student is subject to a criminal investigation involving a school educator, the standard of care owed by school personnel includes informing the student's at-school support system and parents of all developments and limiting discussion among other students to prevent interference with the police investigation. Even though Mr. Moniz was neither Nathan's coach nor his gym teacher, Dr. Leonard still found Mr. Moniz to have breached a standard of care as to Nathan because, despite handing off the prank texts/calls situation to the Jamestown Police, Mr. Moniz continued to pursue his own investigation into Nathan.

To start, Dr. Leonard found that Mr. Moniz ran afoul of his duty to keep the criminal investigation away from the student body by meeting with the football team on February 6, 2018 in which he dangled his resignation as football coach over the players' heads unless Nathan's two coconspirators were identified. Dr. Leonard also found that Mr. Moniz ran afoul of his duty as a member of the school's staff to apprise Plaintiff of various developments involving his child, including his request that Nathan be switched from his gym class for the next trimester, and his ongoing discussions with Mr. Amaral about meeting with Nathan on February 6, 2018 to elicit further information on who else was involved.

The Supreme Court, Education, and the KKK in the 1920s

My new article, The Supreme Court, Education, and the KKK in the 1920s, is about to be published in Western Legal History. The abstract is below, you can download the article here.

Meyer v. Nebraska and Pierce v. Society of Sisters present historians with a puzzle. The Court had refused previous opportunities to initiate a due process jurisprudence that expanded beyond freedom of contract and property rights. Why did the Court suddenly adopt a more aggressive understanding of the Due Process Clause in Meyer and Pierce?

As has been discussed elsewhere, there are several plausible and non-exclusive explanations. This article focuses on the Justices' hostility to the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan had been a leading force behind laws regulating or banning private education, and the Court's decisions in Meyer and Pierce likely in part reflected a pushback against the Klan's agenda.

Part I of this Article discusses the Klan's resurgence in the early 1920s and its role in sponsoring legislation targeting private schools. This included the Oregon compulsory public education law invalidated by the Court in Pierce.

Part II discusses the Court's hostility to the Klan. This section discusses a significant anti-Klan ruling that has received little scholarly attention, the 1928 case of Bryant v. Zimmerman. In Zimmerman, the Court upheld a New York law requiring certain membership organizations, including the Ku Klux Klan, to register their membership lists with the state. The Court held that this requirement did not violate constitutional rights, particularly freedom of association or due process. Importantly, the Court's holding was not based on a rejection of the notion that the Fourteenth Amendment protects the freedoms of private membership organizations. Rather, the Court focused on the malevolent nature of the Klan.

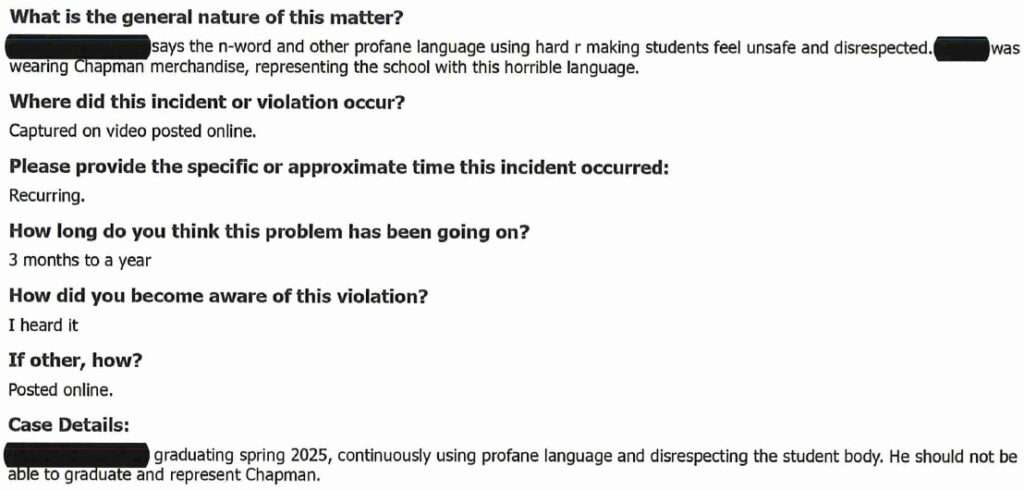

Cancellation Litigation + Doxing Claim, over Allegedly Malicious Publicizing of Snapchat Video with Allegedly Racist Statements

"[B]oth parties exchanged these Snapchat videos while they were intoxicated and their judgment was impaired. Notwithstanding, the communications were private and intended to be jokes between close friends."

From Doe v. Buckley, filed last week in Contra Costa County (California) Superior Court:

Plaintiff and Defendant were close friends in high school and the beginning of college, but had a fallout in July of 2023. During their friendship, they frequently exchanged video and text messages through … Snapchat ….

In December of 2021, during Plaintiff's freshman year of college …, Defendant sent him a Snapchat video while Defendant was partying with some friends at the University of Portland.

Plaintiff sent a Snapchat video reply that referred to Defendant and his friends as his "niggers" …. Defendant had used this same racial slur in his initial Snapchat video to Plaintiff and Plaintiff's reply mirrored the energy and language of the Defendant's message….

[B]oth parties exchanged these Snapchat videos while they were intoxicated and their judgment was impaired. Notwithstanding, the communications were private and intended to be jokes between close friends. Plaintiff never intended anyone other than Defendant to see the Snapchat Video and reasonably expected the private communication to disappear after it was read by Defendant.

"The Clear Winner in Trump v. CASA: The Supreme Court"

"Lower courts lost, and the executive branch got mixed results."

Jack Goldsmith (Executive Functions) is always worth reading, and his article today on the universal injunctions especially so; an excerpt:

Supreme Court "Supremacy" Vis-a-Vis the Executive Branch

Charlie Savage maintained that Trump v. CASA "diminish[ed] judicial authority as a potential counterweight to exercises of presidential power." Ruth Marcus made a similar claim in a piece entitled "The Supreme Court Sides With Trump Against the Judiciary."

These propositions are true only of the lower federal courts. Trump v. CASA did not diminish the Supreme Court's authority vis-a-vis the presidency. The Court held at least that lower courts lacked authority to issue universal injunctions. The Court was ambiguous about whether it could issue universal relief via injunctions. But it made clear in ways that it never has before that it expects executive branch compliance with its opinions and judgments on a universal basis.

Begin with the last sentence of the opinion. At oral argument, Sauer "concede[d] that the 30-day ramp-up period that the executive order itself calls for never started" and that "there should be a 30-day ramp-up period" for the administration to provide guidance. The Court in the last sentence stated: "Consistent with the Solicitor General's representation, §2 of the Executive Order"—which implements the birthright citizenship ban—"shall not take effect until 30 days after the date of this opinion." That sure sounds like a universal injunction! The Court never explains how Sauer's concession got translated into a judicial command, presumably under the All Writs Act. The command is especially unusual since it is directed at a presidential order.

Federal Courts May Not Be Denny's, But They Are Open 24/7/365

Justice Kavanaugh's Trump v. CASA concurrence appears to reply to Judge Ho.

On remand in A.A.R.P. v. Trump, Judge James Ho of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit suggested it was unreasonable to expect federal district courts to be open and available to respond to emergency pleadings at all hours of the night. He wrote:

We seem to have forgotten that this is a district court—not a Denny's. This is the first time I've ever heard anyone suggest that district judges have a duty to check their dockets at all hours of the night, just in case a party decides to file a motion. If this is going to become the norm, then we should say so: District judges are hereby expected to be available 24 hours a day—and the Judicial Conference of the United States and the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts should secure from Congress the resources and staffing necessary to ensure 24-hour operations in every district court across the country.

Whether or not the Judicial Conference and Administrative Office have provided the relevant resources, federal law already requires the federal courts to be open for business around the clock. Justice Kavanaugh makes this point in his Trump v. CASA concurrence, in which he writes:

Some might object that this Court is not well equipped to make those significant decisions—namely, decisions about the interim status of a major new federal statute or executive action—on an expedited basis. But district courts and courts of appeals are likewise not perfectly equipped to make expedited preliminary judgments on important matters of this kind. Yet they have to do so, and so do we. By law, federal courts are open and can receive and review applications for relief 24/7/365. See 28 U. S. C. §452 ("All courts of the United States shall be deemed always open for the purpose of filing proper papers . . . and making motions and orders").

As it happens, judges (and justices) are often expected to be available throughout the night, such as when there is a pending execution and last-minute stay requests or other filings can be expected. Granting of such requests can also prompt middle-of-the-night responses (as occurred here). If such proceedings are expected in the context of capital sentences, it is not altogether clear why they should not be expected where the government is preparing to permanently remove someone from the United States and send them to a foreign prison, particularly if there are reasons to believe the government is racing to act before courts can intervene. Regardless, whether we should expect late-night proceedings in the context of deportation, federal law deems federal courts are "always open," even if most filings do not need to be considered on anything remotely approaching an expedited basis.

So while a district court may not be a Denny's, it is formally open to hear business 24/7/365.

Supporting Free Speech and Countering Antisemitism on American College Campuses

The final version of this article is available for download here.

Coauthor David L. Bernstein and I spend a fair amount of space recounting examples of antisemitic campus activity that did not involve protected speech, such as vandalism, classroom and library disruptions, threats, one-on-one verbal harassment, assault, and more. Some readers of the draft paper questioned why a paper on free speech and antisemitism talking about things that don't constitute free speech.

A major reason for doing so is that David L. and I saw that many commentators were portraying the complaints about antisemitism on campus and the antidiscrimination obligations of universities under Title VI as if these complaints solely or primarily revolved around controversial political speech such as "From the River to the Sea, Palestine will be free."

A case in point is the just-published Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and Title VI: A Guide for the Perplexed, by lawprofs Benjamin Eidelson and Deborah Hellman. The authors barely address the obviously illicit nature of many of the activities alleged to be antisemitic, and incidents of assault, threats, and more are not addressed in their article.

Relatedly, the authors give extremely short shrift to the concern that the way universities have handles these activities reflects illegal disparate treatment of Jewish students. David L. and I write that the authors claim:

a university may defend a claim based on double-standards by arguing that most "claims by Jewish students are enmeshed with hotly disputed views about world affairs means that efforts to accommodate them may pose risks of chilling political speech or intruding on academic freedom that are less acute in many other cases."

The "natural comparator," therefore, would not be how the university treats discrimination claims in general, but how it treats "claims of discrimination and exclusion raised by Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim students."

In fact, claims of discrimination are often "enmeshed with hotly disputed views" on hot-button political issues (e.g., affirmative action, abortion, same-sex marriage), and if a university is applying a double standard to Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim students, the correct solution is to stop doing so, not to also discriminate against Jewish students.

Moreover, responding to disruptions, assaults, threats, and so on, does not impinge on protected speech to begin with, so recognizing that many claims of antisemitism are not about viewpoints but about illicit actions would make the threat of "chilling political debate" far more remote.

Justice Kagan on Universal Injunctions in 2022

Justice Kagan said "it just can't be right" that a single court judge can stop a federal policy in its tracks nationwide.

Back in 2022, while speaking at the Northwestern University Law School, Justice Elena Kagan addressed the issue of universal injunctions, in the context of noting how the issuance of such injunctions forced the Court to consider more questions on an expedited basis through the emergency docket. Politico reported on the comments at the time, as noted by Sam Bray here.

Based upon the video, here are her remarks:

in in recent years some district courts have issued nationwide injunctions, and this happened in the Trump administration and it has also happened in the Biden administration so this has no political tilt to it, but some district courts have, you know, very quickly issued nationwide injunctions to stop a policy in its tracks that . . . the President and/or Congress has determined to be the national policy, and it just one district court stops it, and then you combine that with the ability of people to forum shop to go to a particular district court where they think that that will be the result and you look at something like that and you think that can't be right that one district court, whether it's in you know in the Trump years people used to go to the Northern District of California and in the Biden years they go to Texas, and it just can't be right that one district judge can stop a nationwide policy in its tracks and and leave it stopped for the years that it takes to go through normal process.

One question is what Justice Kagan meant by saying that "it just can't be right that one district judge can stop a nationwide policy in its tracks and and leave it stopped for the years." Was this merely a policy view -- that allowing individual district court judges such power is no way to run a railroad -- or was it a view of the law? And, if the latter, did Justice Kagan's view change? Was she persuaded by the briefing, subsequent academic scholarship or Justice Sotomayor's dissent? Or was there something about Trump v. CASA that justified an exception from a more general rule? As Justice Kagan did not write separately in that case (and, indeed, did not write much this term), I don't think we know.

The full video of Justice Kagan's remarks is available on YouTube, and embedded below. The relevant portion begins around the 40-minute mark.

Trump Administration Targets Iranian Christians for Deportation

They face severe persecution if deported to Iran.

Christianity Today reports that the Trump Administration is targeting Iranian Christian migrants for deportation:

On June 19, as Iran and Israel exchanged volleys of missiles and officials secretly finalized plans to dispatch American bombers to strike Iranian nuclear sites, pastor Ara Torosian published a letter to his church.

Torosian, an Iranian pastor at Cornerstone West Los Angeles, leads the church's Farsi-speaking congregation. He came to the United States as a refugee 15 years ago after being imprisoned for his faith. He has always carried in his heart a prayer, Torosian wrote: "that Iran would be free…."

But five days later, the suffering of his loved ones came suddenly very close.

On Tuesday, the pastor recorded on his phone as masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents arrested two of his church members on a Los Angeles sidewalk. The Iranian husband and wife had pending asylum cases, according to Torosian. They fled Iran for fear of persecution for being Christians and had been part of his congregation for about a year.

The detentions add to a growing number of church members and Christians seeking religious protection who get picked up by ICE. Often they have no apparent criminal history. In many instances, they were in the United States lawfully, complying with orders from immigration courts. ICE has traditionally not deported individuals with pending asylum petitions, who are allowed to work while their cases proceed.

If deported back to their country of origin, Iranian Christians face severe persecution at the hands of Iran's radical Islamist theocracy. That persecution has actually intensified in recent years, and includes criminalization of the promotion Christianity, and severe punishments for Christians considered to be "apostates" from Islam. This persecution makes Iranian Christians obvious candidates for asylum or refugee status (for which applicants are eligible based on persecution on the basis of religion, among other possible criteria). At the very least, those who have filed such applications must not be deported until those applications have gotten proper consideration.

I'm old enough to remember a time when conservative Republicans saw themselves as defending Christians against radical Islamism. Today, a GOP administration wants to deport Christians to persecution by a radical Islamist regime. The only people Trump considers worthy of refugee status seem to be white Afrikaner South Africans. While they may have a plausible case (and I don't oppose admitting them), that of Iranian Christians - and many other severely oppressed groups - is much stronger

Sadly, this is far from the only situation where the Trump Administration seeks to deport migrants who fled oppression by the types of regimes conservative claim to especially oppose. The same story plays out in efforts to strip legal status from Afghans who fled the Taliban (including many who aided the US during the war), and Cubans, Venezuelans, and Nicaraguans who fled socialist dictatorships.

People who genuinely oppose socialism and radical Islamism would not close the doors against those regime's victims. Doing so is both unjust and harmful to the US economy (to which these immigrants contribute) and to America's struggle in the international war of ideas against these regimes. It's hard to credibly tell people we are better than these brutal despots when we callously deport their victims back to them, thereby facilitating the very oppression we claim to oppose.

Congratulations to Jonathan Adler, Cited in Two Supreme Court Opinions Over the Past Two Weeks

His and Chris Walker's Delegation and Time was cited in Justice Gorsuch's dissent yesterday in FCC v. Consumers' Research and his Is the Business of the Court (Still) Business? was cited in Justice Jackson's dissent last Friday in Diamond Alternative Energy v. EPA.

Bray and Bagley on Trump v. CASA

Two worthwhile commentaries on the Supreme Court's decision to curtail universal injunctions.

There has been quite a bit of quick commentary on the Supreme Court's decision to curtail the entry of universal injunctions in Trump v. CASA, much of it generating more heat than light (including that offered by President Trump). This post highlights two essays on the decision that are worth the read.

First is an op-ed by Samuel Bray in the New York Times, "The Supreme Court Is Watching Out for the Courts, Not for Trump." Professor Bray has been among the most persistent and important critics of universal injunctions and Justice Barrett relied upon his scholarship in her decision. In his op-ed, he gives his read of the decision, explains why it is unlikely to allow President Trump's unlawful Birthright Citizenship Executive Order to ever take effect, and explains why he thinks it "gives the courts a chance to reset, and to shift toward the more deliberative mode in which they do their best work." He notes that the decision surfaces "competing visions for the role of the courts in our constitutional system."

One vision is to say that the job of every judge is to declare the law and make sure everyone, including the president, follows it all the time. There's a lot to be said for following the law, and in our constitutional system, no one is above it.

Another vision is to say that the chief job of the courts is to decide cases. Resolving disputes is what gives the courts their legitimacy: It is the core of the judicial power given by the Constitution, and robust judicial power is tolerable in a democracy precisely because the judges stay in their lane. A judge's job is not to say, "Someone is wrong on the internet" and then do something about it. Instead, her job is to decide the case before her fearlessly, according to the existing law, and to give the proper remedy to whichever party wins.

As should be clear, the Court has embraced the latter conception. Indeed, Justice Barrett rejected Justice Jackson's explication of the alternative vision quite forcefully.

Bray adds:

We live in a time of great pressure on our constitutional system, with a president who thinks he can make laws (he can't), suspend laws (he can't) and punish enemies without a trial (he can't). It is precisely at this time that the first vision is most attractive — and the second vision is most essential.

The courts must defend constitutional rights and liberties. But they must defend them as courts defend them: deciding cases for the parties and giving remedies to the parties. That function is what gives courts their constitutional legitimacy in a democratic society.

It will mean that courts don't have the power to remedy every wrong. And it will mean that a patchwork of rulings sometimes persists. But to remedy every wrong immediately and everywhere — outside of the case and the parties — is not what the courts are designed for.

Another commentary worth reading is by Nicholas Bagley, who has also long been critical of universal injunctions, albeit from the Left. (He testified against them in 2020.) In an Atlantic essay, "The Supreme Court Put Nationwide Injunctions to the Torch," he suggests his fellow progressives should be more supportive of the Court's decision.

Although the Supreme Court divided along partisan lines, with the liberal justices dissenting, I don't see this as a partisan issue. (The outrageous illegality and sheer ugliness of President Donald Trump's executive order that lies underneath this fight may go some distance to explain why the three liberals dissented.) Nationwide injunctions are equal-opportunity offenders, thwarting Republican and Democratic initiatives alike. Today, it's Trump's birthright-citizenship order and USAID spending freezes. Yesterday it was mifepristone, the cancellation of student debt, and a COVID-vaccine mandate. Why should one federal judge—perhaps a very extreme judge, on either side—have the power to dictate government policy for the entire country? Good riddance.

Like Bray, Bagley notes the range of relief that will still be available to litigants, such as through class actions and (unfortunately) under the APA. He also sees universal injunctions as a symptom of broader problems in our legal culture that may take longer to fix.

Nationwide injunctions are a symptom of a legal culture that affords judges a central role in American policy making. Without changing that legal culture, and the many different laws and doctrines that underwrite it, any single change—even one as significant as ending nationwide injunctions—will yield only a modest course correction.

Free Exercise Clause Rights to Opt Children Out of Public School Lesson That "Substantially Interfer[e]" with Their Children's "Religious Development"

[1.] The Supreme Court has been debating the meaning of the Free Exercise Clause for over 60 years. One view has been that the Clause generally gives religious objectors a presumptive right to be exempted from generally applicable laws, such as from bans on using peyote, requirements that one provide one's child's social security number to get various welfare benefits, requirements to provide certain health insurance to one's employees, and anything else that might conflict with one's religious beliefs.

This right was just a presumption, which the government could rebut if it has a strong enough reason. And indeed the presumption was often found to have been rebutted, in cases involving draft laws, tax laws, antidiscrimination laws, child labor laws, and more. But the presumption, though not very strong, was broad: It applied to a wide range of religious practices. Historically, that view had been associated mostly with the liberals on the Court, such as Justices Brennan and Marshall. The leading precedent here was Sherbert v. Verner (1963), written by Justice Brennan.

The opposite view has been that the Clause only forbids discrimination targeting religious believers or practices (such as laws that ban religious animal sacrifice but allow virtually identical secular killing of animals, or laws that exclude religious schools from various benefit programs that are offered to secular private schools). Historically, that view had been associated mostly with the conservatives on the Court, such as Justice Scalia and Chief Justice Rehnquist. The leading precedent here was Employment Division v. Smith (1990), written by Justice Scalia.

Curiously, the ideological polarity on this matter has flipped in recent years, with the Court's conservatives generally endorsing the traditional Brennan/Marshall view, and the liberals generally endorsing the Scalia/Rehnquist view. It looked, from cases such as Fulton v. City of Philadelphia (2021), like there were at least five votes on today's Court to bring back the broad-exemption-rights view.

But in today's Mahmoud v. Taylor, the conservative majority took a different approach: Rather than discussing government actions that interfere with religiously motivated behavior generally, it focused on a particular kind of government action—educational rules that substantially interfere with parents' ability to "direct the religious upbringing of their" children. And while this is just a narrowly defined Free Exercise Clause right (focused just on interference with religious upbringing), the protection appears to be quite strong.

Show Comments (499)